The Dungeons & Dragons experience can be broken down into three core pillars of gameplay: combat encounters, social interactions, and exploration. Viewing the game this way gives you useful building blocks when writing your campaign. But while combat and social encounters often take center stage, exploration can often be a vague and overwhelming aspect of the game.

In this article, I will share a method I refer to as dungeon-based design to make exploration fun to engage with as a player and easier to prepare as a Dungeon Master.

- What Is Dungeon-Based Design

- From Towns to Nations: Scaling

- Time, Challenges, and Risks

- Example Design: The City of Erdwile

Social Interaction vs. Roleplay

Through this article, you’ll see very little mention of "roleplay," and instead, I’ll be using the term "social interaction." While roleplay is often listed as a pillar of gameplay, this sometimes creates the false impression that roleplay is somehow mutually exclusive from combat or exploration.

I want to emphasize that you can roleplay as part of any of the three pillars, so I’ll be using "social interaction" rather than "roleplay" when referring to the aspect of gameplay that involves interacting with PCs and NPCs.

What Is Dungeon-Based Design?

Dungeon-based design is an approach to designing engaging exploration that is, unsurprisingly, inspired by the design of dungeons. Your classic D&D dungeon is an excellent example of a node map for players to explore. Let's take this dungeon map presented in Appendix C of the 2014 Dungeon Master's Guide. At first glance, it seems to be a relatively complex arrangement of rooms and corridors.

However, if you treat each room not as part of a larger map but as an individual encounter that can stand alone, you can represent each room as a single point, a node.

This allows you to map out the possible routes between them, not how they're shaped by the dungeon, but as straight lines. The twists and turns of the caverns and corridors are a descriptive aspect of the dungeon rather than a strict element of the design, and pulling this back can let you view the dungeon in a much more abstract manner.

This is the core of what I mean by dungeon-based design; this node map is an accurate representation of how the players can navigate this dungeon. But if I take the dungeon image and change it for a settlement map, now instead of a layout of rooms and corridors, it's streets and neighborhoods.

But what is a node? A node is just a point where multiple paths meet. It's anywhere that you can expect your players to reach through multiple routes or depart via multiple options. It's where you can place challenges for your players to overcome, which I will get into next.

So, with this approach, you can view any form of exploration as being the structure of a dungeon but with a different descriptive layer over the top, like a skeleton in a trench coat. This one is a skeleton wearing a city trench coat, while another could be a skeleton wearing a world map trench coat! It's all skeletons, all the time!

From Towns to Nations: Scaling

As I've mentioned a few times so far, you can scale this approach up from dungeons to almost any level of exploration, even as far as a map of the planes of the multiverse. It's a case of identifying what your nodes are and what logical paths would exist between them.

For dungeons, the nodes are rooms or caves, and the paths are corridors or tunnels. The next step up in scale would be a large village or town, somewhere just big enough that going from location A to location B isn't just the case of a straight line. Dungeon-based design doesn't work well when there aren't limitations on what paths you can take, so small villages and hamlets aren't well-suited.

However, with larger villages or small towns, the high density of buildings can justify having specific routes. At this scale, the nodes are key buildings such as the tavern or town hall, and the paths are streets or roads.

Zooming out one step further, we have large towns and cities. The paths are still essentially the same, albeit on a bigger scale; instead of a path representing a single road or path, it's now a series of roads or a main highway running through the city.

But what has changed is what the nodes represent; instead of specific buildings, they now stand in for entire neighborhoods. Rather than the tavern, a node might represent the entertainment district, or instead of the town hall, it's the administrative area.

This allows you to put a lot more into a single node, and your players could spend an entire session exploring what it offers. I would advise keeping everything on theme and not overloading things. If you have a shopping neighborhood, limit it to two or three shops and keep them similar in nature. You can always have more than one; perhaps one area is the jewelry quarter, while another is the smithing quarter.

Beyond the city map, we have the world map where the nodes are settlements and other points of interest, while paths are highways, major roads, and commonly used routes through dangerous terrain such as mountains or forests.

But the scale doesn't stop here; you can go well beyond the world map. I've made maps of Wildspace systems with safe routes between them and even maps of the multiverse with paths detailing portal connections.

Time, Challenges, and Risks

Once you've got your dungeon-based design for your town, city, world map, or Spelljammer Wildspace chart, how do you make exploration engaging? Much like there are three pillars of D&D gameplay, there are three pillars of exploration: resources, risk, and challenges.

Time As a Resource

Resources cover anything the party can access that is used up by exploring and can run out, resulting in negative consequences. The most common resource in the context of exploration is rations, but I prefer to focus on a different resource: time.

Regardless of what the party is exploring, time is the one constant resource they will need. The party might not need food or water in a town or gold to bribe people in a dungeon, but they will always use time with everything they do.

As such, it can be beneficial to establish a unit of time that each action will consume while exploring. For example, actions in a dungeon might use a 10-minute unit of time, representing the average time spent moving between chambers, exploring a room, fighting a combat encounter, or picking a lock.

However, when navigating a world map, you might use an 8-hour unit of time or possibly even 24 hours. Whatever you feel reasonably represents how much time the party might spend on average doing any possible action on the map.

But what possible actions would the party have at their disposal? Generally speaking, possible actions can be broken down into:

- Move

- Explore

- Interact

- Overcome obstacles

- Rest

This list broadly covers what the player will typically expect to do when exploring a region and can be tailored to suit almost any environment. It just becomes a matter of describing these actions in a way that matches the unit of time you're using.

Resting at a dungeon scale of 10 minutes per action might mean taking six actions in a row to take a long rest, while at a city scale where it's 4 hours per action, resting would be two actions to take a long rest. That's why it's helpful to establish your units of time before deciding on the nature of the actions players can take.

One of the above listed actions is overcoming obstacles, leading to the following two elements of exploration: risks and challenges. Risks and challenges represent means of engaging with the character's skills and abilities and potentially depleting more resources such as hit points, spell slots, potions, and other limited-use abilities.

Risks and Challenges

In the context of dungeon-based design, an exploration risk is a course of action that can potentially have a negative outcome, with the chance being proportional to the benefit of taking that risk. For example, a shorter route saves time but with a higher chance of having a deadly combat encounter than taking the longer route.

On the other hand, a challenge is an obstacle that bars the party's way of advancing toward their goal and must be resolved through one or more possible means. Risks can be engaged at the party's discretion, while challenges must be overcome.

Typically, you want to place risks along the paths of your node map and challenges at the nodes themselves. Risks can be used to encourage your players to take alternate routes around the overall map and incentivize exploration. In contrast, challenges can be used to control the rate at which they advance through the overall goal of exploration.

That's one of the things I like most about dungeon-based design; it gives you, the DM, lots of tools for influencing the pace of the game and where the party goes without taking away their agency. You can say, "I'd like for you all to explore this village over here," but you're not forcing them to, and if they want, they can choose to risk fighting giants as they take a shortcut through the mountains. It strikes that balance between player agency and DM control that can be challenging.

Sources of Inspiration

As for what kinds of risks and challenges you can present, this is where we can reevaluate the two other pillars of D&D: combat encounters and social interactions. Combat encounters make for natural risks. You may deal with rampaging trolls, a bandit-plagued highway, or a dragon's lair.

However, traps and environmental hazards can also make for excellent risks. If you'd like some inspiration, Chapter 5: Adventure Environments from the Dungeon Master's Guide and Chapter 2: Traps Revisited from Xanathar's Guide to Everything are particularly useful.

Social interactions and puzzles make for wonderful challenges for the party to overcome when they reach a node. The party needing to convince a council member to let them pass through the gatehouse or answer a sphinx's riddle can provide an engaging barrier to advancement without the immediate threat of a combat encounter.

Something important to making challenges that are engaging rather than frustrating is giving the players the ability to step away from the challenge and circle back later. Nothing ruins a puzzle or social interaction more than the players being stuck there until they solve it. For some resources on these challenges, I recommend rules on Social Interaction in Chapter 8 of the Dungeon Master's Guide and Puzzles in Chapter 4 of Tasha's Cauldron of Everything.

Example Design: The City of Erdwile

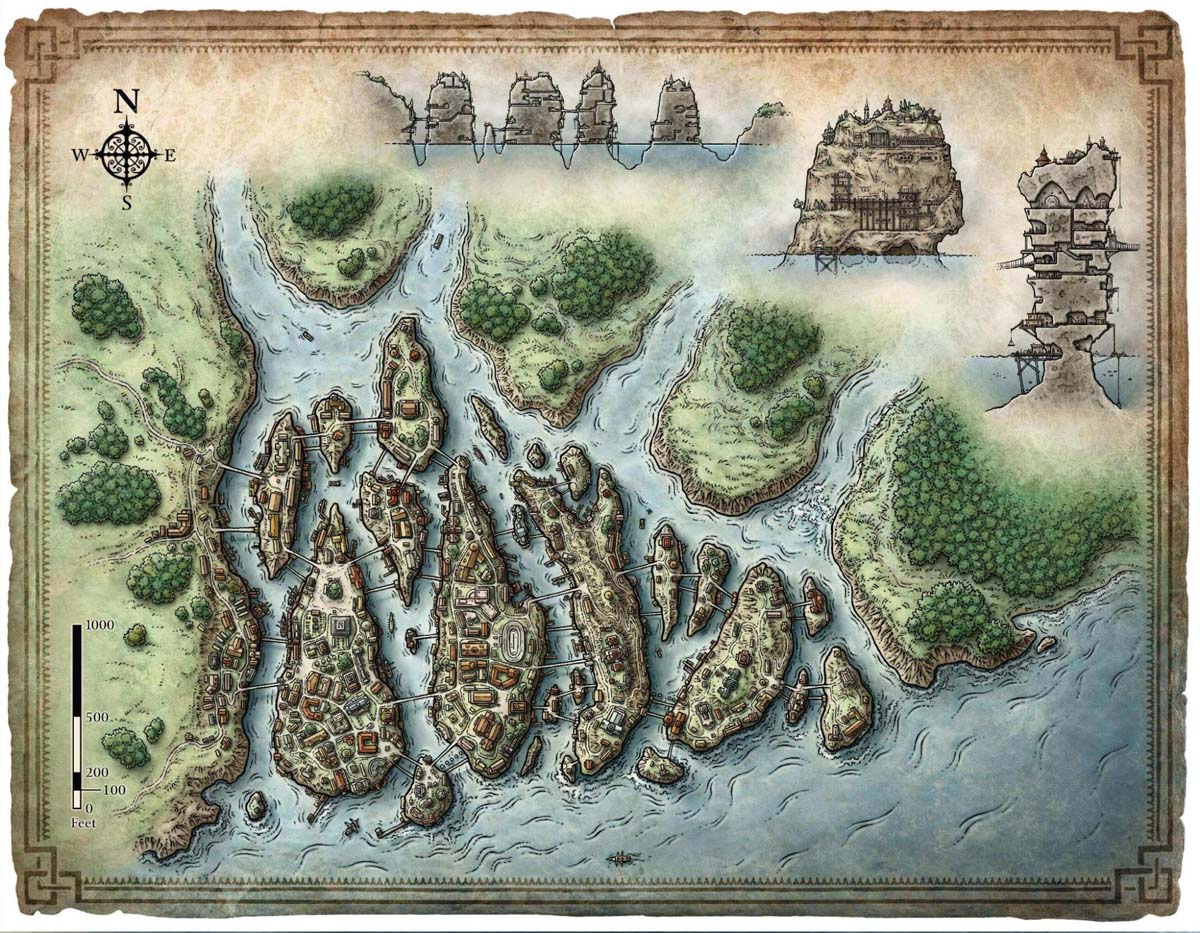

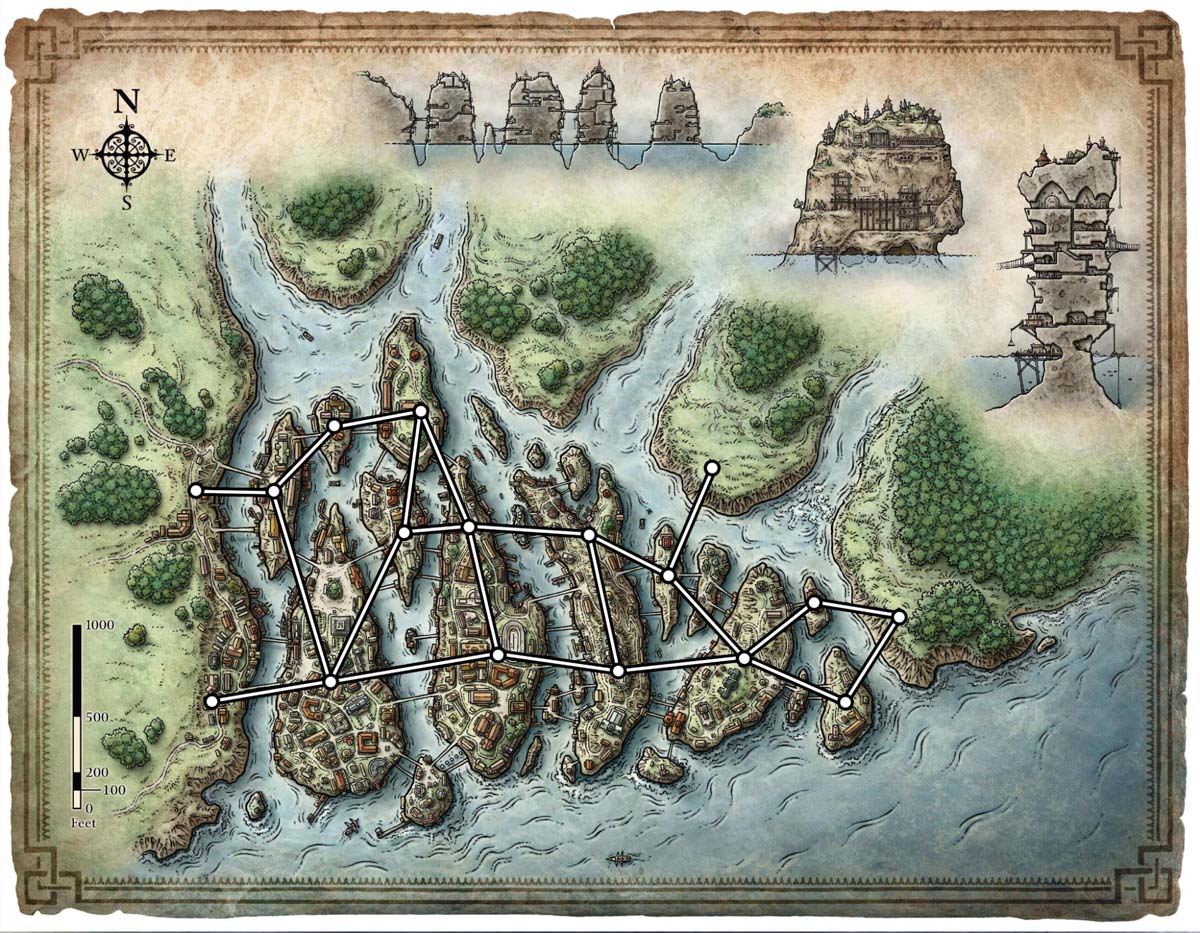

Now that we've established the fundamentals of dungeon-based design, let's put it into action and make an exploration map for the City of Erdwile. We'll be using one of the maps found in Appendix C of the Dungeon Master's Guide as our starting point.

To set the scene, the players are traveling east, carrying an important message from the king of Borchanne that could signal the war's end with the neighboring nation of Tal'ryn. However, the treacherous river Erd lies in their way, and the only way to cross the river within the limited time they have to deliver the message is to pass through the City of Erdwile.

Erdwile has been doggedly neutral in the war and isn't willing to let involved parties pass, even if they carry a message of peace. The players must find a way through Erdwile without wasting too much time as other agents move against them.

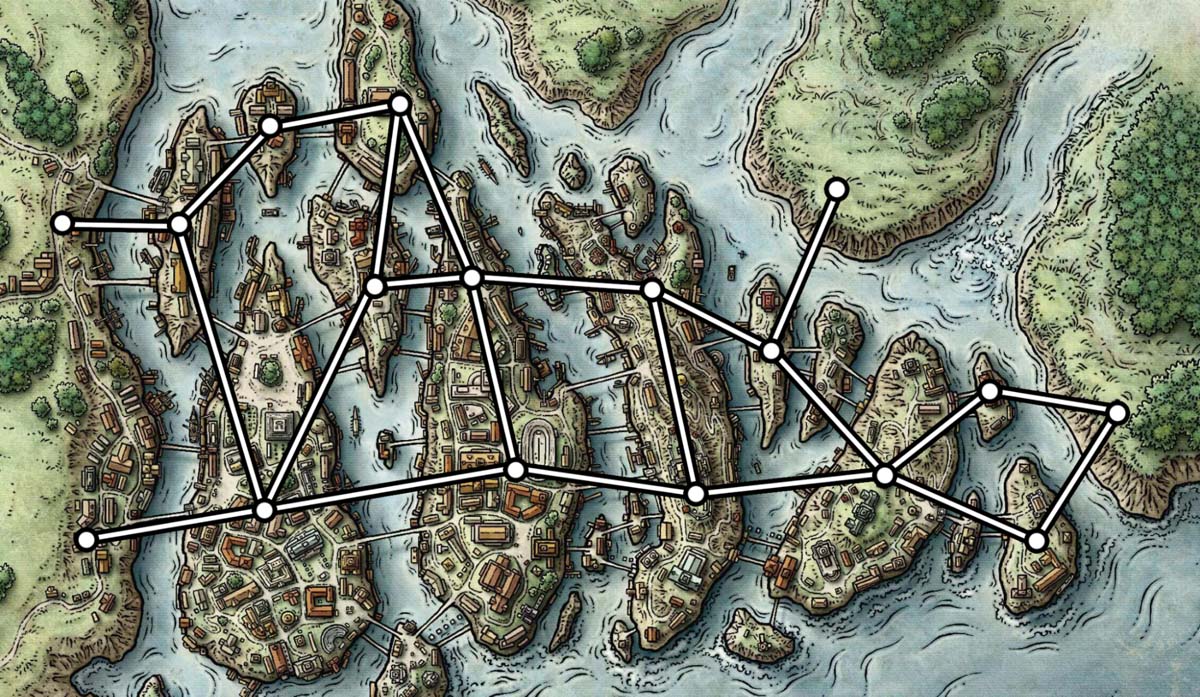

Here is the map we will be starting with:

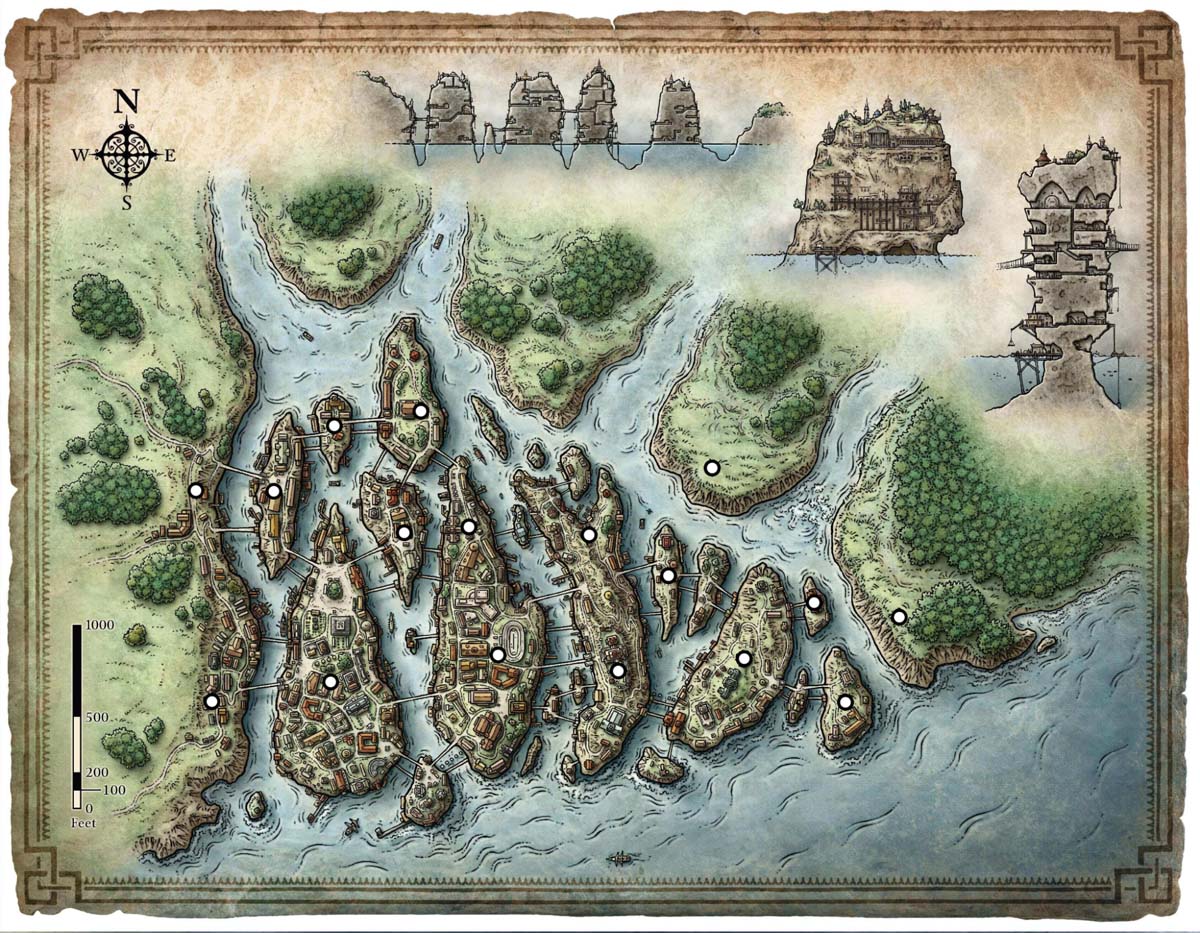

Our first step is to mark the nodes—key locations the party will pass through and encounter challenges at. We can do this based purely on aesthetics. What looks interesting on the map and will make for an evenly spread-out layout of nodes? Let's go with this:

Now, we need to connect the nodes representing city neighborhoods with paths. Some storytelling begins to emerge here as some paths represent bridges crossing the dangerous waters. This will start laying some groundwork for the risk the players might face.

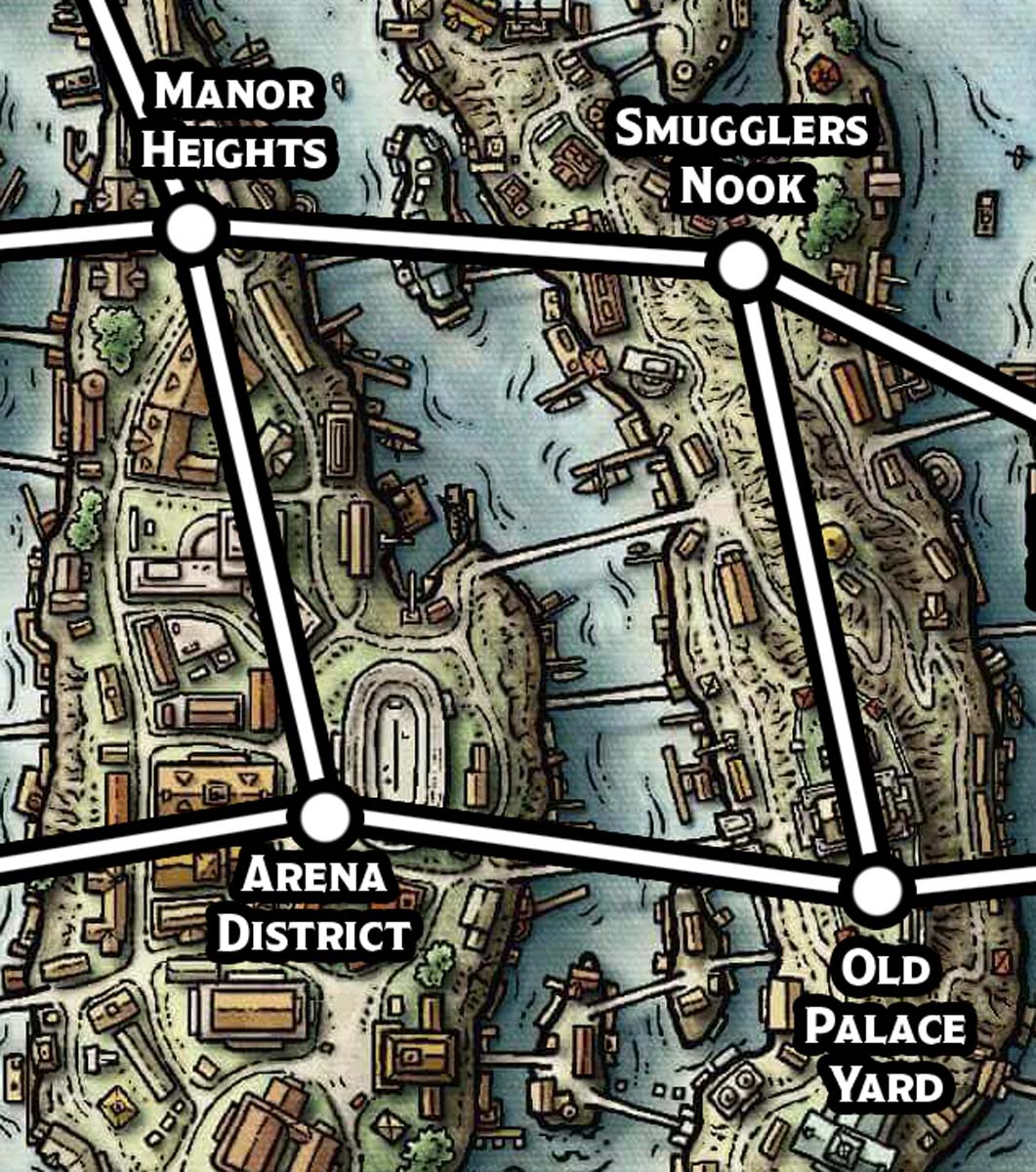

With the basic node map of the city done, we can add some detail by naming the neighborhoods and other regions. Rather than do the whole city, I'm going to zoom in on this section:

Here, we have four neighborhoods (nodes) with four routes (paths) between them, so we need up to four challenges and some risks.

The challenges the players face can provide storytelling opportunities:

- Perhaps to pass through the Arena District without being accosted by guards, they must masquerade as gladiators and compete in the arena.

- For Old Palace Yard, the party must steal documentation from the watch house to take to Smugglers Nook and get forged into passes.

- In Manor Heights, they are accosted by the private guards of an arrogant noble who assumes the party is a group of thieves, and now they must prove their innocence by finding the real thieves.

We can also think about the unit of time the players will have to complete their actions. Based on the size of this city and some of the challenges we've come up with, a unit of 1 hour seems reasonable. This means the players can accomplish a reasonable amount per day while still feeling time pressure.

Now, we can look at risk. The routes between Old Palace Yard and the Arena District and between Smugglers Yard and Manor Heights involve crossing bridges. One could be a safe route with a high toll for the players to pass at the south versus a dangerous and rickety bridge that is intentionally poorly maintained to try and limit travel between the affluent Manor Heights and the lawless Smugglers Nook neighborhood.

This gives the players a meaningful risk/reward decision between safe but expensive and dangerous but free.

Meaningful Risk/Reward Balancing

The key to risk/reward balancing in exploration design is meaningful decisions. Choosing between something easy with no downsides and something hard with some downsides is not a real choice. There has to be a real reason to take the difficult option.

Maybe it’s quicker or cheaper, or there’s a chance of finding some loot or a magic item. There must be a motivation to do things the hard way that balances the risk of doing so.

Mapping Your Exploration

Dungeon-based design can be a valuable tool for creating engaging exploration experiences in your D&D games.

For me, what has made it a go-to tool when writing out an adventure is its scalability. I can use it to design challenges in a small town or map out the planes of the multiverse. I'm currently using it in a level 20 arc of my seven years (and counting) campaign as my players explore dangers and mysteries in the drow city of Menzoberranzan. I hope it proves as useful to you as it has been to me!

Davyd is a moderator for D&D Beyond. A Dungeon Master of over fifteen years, he enjoys Marvel movies, writing, and of course running D&D for his friends and family, including his daughter Willow (well, one day). The three of them live with their two cats Asker and Khatleesi in south of England.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This is fascinating! I think I’ll be using this for my next city!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024I love this approach, I always try to give options/choice to my players and this is one way to do it. It also brings it closer to a game concept (if this is what you want, it works!)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Interesting

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This is genuinely such a useful article, thank you so much. We need more DM tips like this!!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Wow, the one time I don’t need to build a city it pops up

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This is actually really cool, I think I am going to incorporate this in my next campaign I am going to be running.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Very interesting. This was a great article and useful for DMs. Hope more articles like these come through.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Inverting what I normally think of as point crawls to show them as a dungeon variant will really help how I communicate to players. Plus since I'm bad at map making I love nodes and passages!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Anyone who likes this and is interested in this style should really check out The Alexandrian blog

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Really good article

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Excellent article. Thank you!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This is a great article! I hope to see more like it!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This is exactly the content I want from these articles, what an interesting write up that is useful for all levels of experience.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Amazing Article helped me a lot.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This entire write up should be in the DMG! Thank you Davyd!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024This is a brilliant article really engaging and useful, thank you.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024That island chain city map looks awesome. Are those available anywhere in DnDB?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Excellent article! This is really useful, thank you!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Great article!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 19, 2024Best gaming article I have read in years! Thanks Davyd.