Welcome to New Player’s Guide, the first stop on your journey to playing D&D. This series has advice for players who’ve just joined their first D&D campaign, as well as Dungeon Masters who want help taking their new campaign to the next level. To see the other articles in this series, check out the New Player’s Guide tag—and for the brass-tacks information on how to start playing D&D, click on the New Player Guide link at the top of this page!

This installment of the New Player’s Guide series is for Dungeon Masters who are running their first campaign. You may have already chosen your first adventure, and you may have even started developing future adventures, but there’s one big problem. The world. When most DMs run Lost Mine of Phandelver, it tends not to matter that the adventure is set in the Forgotten Realms, since Phandalin is so sectioned off from the rest of the world. Now that your adventure is expanding beyond that simple frontier town, you need to make a decision: are you going to keep playing in a published setting, or create your own world?

Why Use a Published Setting?

There are pros and cons to both using published campaign settings and homebrewing your own. Homebrewing a setting is a lot of work, and you’ll end up doing a lot of research into real-world history if you want to create a world that feels natural. Using a published setting like the Forgotten Realms means that you will never want for material to draw upon as inspiration. There are books like Sword Coast Adventurers Guide which describes the lands of the Sword Coast, and adventures like Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur’s Gate: Descent into Avernus, and Storm King’s Thunder also act as mini-setting guides for the locations that their stories take place in. Since the Forgotten Realms are the default setting of D&D—that is, it’s where most of its published adventures are set—it’s easy to run a published adventure, or mix and match bits and pieces of one, without causing any lore problems.

However, if you’re planning on running your own homebrew campaign, the baggage of a published campaign setting could get in your way. Just as it’s a lot of work to research enough about the real world to create a brand-new setting of your very own, it’s nearly as much work researching the fictional world of the Forgotten Realms to run a lore-faithful campaign in that world! The Realms have been in print since the late ‘70s, and there have been hundreds of thousands of words written about it. The weight of canon is heavy, and even though D&D is a game that encourages you to make your own stories, canon be damned, some DMs will always be a nagging urge to remain accurate to lore. The books encourage you to silence this voice, but it’s a persistent demon of the mind.

And this is just issues of canon, like “how common are dragons in the Realms? What if I want them to have disappeared from the world and suddenly returned, like in Skyrim?” or something like that. Settings with lots of history are festooned with lore characters of incredible power—and none is as infamous as the epic-level wizard Elminster. Every campaign set in the Realms must answer the question, “Why isn’t Elminster solving this?” (A good answer is, “he’s off solving an even worse problem halfway across the planes right now.”) But even if you can excuse away the lack of intervention from high-level NPCs, it may still feel like an excuse.

Newer settings, like Eberron or Wildemount feel the tyranny of canon less heavily than the Realms, but the weight isn’t completely gone. Creating your own campaign setting frees you from the burden—be it real or imagined—of adhering to canon. It also lets you pillage freely from any campaign setting. Want the robotic warforged and shapeshifting changeling races from Eberron: Rising from the Last War, but don’t care about the lore? Just buy them individually through the D&D Beyond Marketplace for two dollars each. In that way, if you didn’t like the official Eberron lore for warforged or changelings, you can create your own and still provide your players with the ability to make warforged or changeling characters in the D&D Beyond Character Builder.

So, what’s your choice? Do you want your first campaign to take place in a setting where all the work is done for you, but you have to look that information up? Or do you want it to take place in a setting where you have to do all the work, but it can be exactly the way you want it to be? If you chose the second option, read on, here’s how you do it. And read on even if you chose the first option—there’s plenty of info below that will make it easier for your players to learn the setting you chose, too!

Start Small

The best advice on setting creation anyone can give is “start small.” Put another way, the biggest mistake that most first-time worldbuilders make is by starting too large. A D&D world can be as big as you can imagine, so it’s easy to bite off more than you can chew. You can waste a lot of time at the beginning of your campaign by focusing on details that won’t be important to your campaign for weeks, months, or even years. Nation-scale geopolitics, gods and archfiends, the planes themselves—these things are all very fun to think about.

Unfortunately, for most DMs, they’re a waste of time. A lot of D&D campaigns sputter out around the three-month mark, as the game loses that new-campaign shine and people return to focusing on school, their job, or their social life outside of the game. If your game started with all the characters at 1st level, then three months of play will probably make them 5th level at most. All of the hard work you put into nation-level stuff that probably won’t come up until you pass 5th level is wasted. Or, you’ll have to put it in a folder and repurpose it later with a different group. Either way, it’s frustrating.

So start small. Intentionally put limits on your creativity, so that you can make the small-scale beginning of your campaign as exciting as it could be. Oh yeah, that’s the other factor for a group breaking down: when the group loses interest in the small-scale stuff. All the cool gods and geopolitics in the world won’t save a D&D group if they can’t find anything interesting to interact with on their level—and it’s clear to players when the DM doesn’t care about that either. That’s when fatigue sets in and players start missing sessions. No one is to blame in this situation, but there is something you can do about it.

Creating a Settlement

Where does your first adventure start? For most campaigns, that’s a town like Phandalin in the Starter Set adventure Lost Mine of Phandelver and the Essentials Kit adventure Dragon of Icespire Peak. Phandalin in either adventure is great inspiration for any DM interested in building their own campaign world. Look at the scale of the map; the entire town is less than 1000 feet across, and half that number wide. It has 30 or 40 houses, and less than a quarter of those places are points of interest for adventurers. When creating the town that your adventure will start in, consider including each of these five types of locations. These places are all common destination for adventurers, so having them prepared ahead of time will help you improvise when your players want to ignore your quests and explore the world you’ve created.

Where does your first adventure start? For most campaigns, that’s a town like Phandalin in the Starter Set adventure Lost Mine of Phandelver and the Essentials Kit adventure Dragon of Icespire Peak. Phandalin in either adventure is great inspiration for any DM interested in building their own campaign world. Look at the scale of the map; the entire town is less than 1000 feet across, and half that number wide. It has 30 or 40 houses, and less than a quarter of those places are points of interest for adventurers. When creating the town that your adventure will start in, consider including each of these five types of locations. These places are all common destination for adventurers, so having them prepared ahead of time will help you improvise when your players want to ignore your quests and explore the world you’ve created.

- A place of guaranteed safety

- A place to find something to do

- A place to buy gear

- A place to spend money for pleasure

- A place unique to that town

These are gameplay fixtures for your town. They will help you make your game run more smoothly. With those brass-tacks features in place, consider the storytelling details of your settlement.

- Who lives here?

- What problems does this settlement have?

- Where is this settlement, in terms of climate and geography?

- When was this settlement founded?

- Why was this settlement founded?

With these storytelling details in place, you should have enough information written down to improvise an answer to just about any question your players ask you about the town. This information will also work as fuel for the fire; you’ll have a clear picture of the place in your head, and your imagination will start working in the background.

If you want more advice on how to create a settlement-sized area for your D&D campaign, check out the Settlements section in chapter 5 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Ten-Mile Zone

Now that you have a settlement created in your mind, you can expand your world into a 10-mile diameter area around that location. This is a small bite of territory, just enough for adventurers to explore while using the settlement you’ve created as home base. Home bases are vital for adventurers, since they give them a place where they can be safe from danger, pick up more quests, or even just hear rumors about other nearby locations they can explore.

The first thing you should do when creating the wilderness surrounding your settlement is to draw a simple map. This will help you (and eventually your players) be able to visualize what the world looks like, rather than imperfectly imagining it. Start your map with square graph paper—even though this advice says a ten-mile diameter, it’s simpler to make a map that’s 10 squares tall and 10 squares wide than to create an actual circular diameter. Old-school gamers and published adventures tend to use hexagons or “hexes” instead of squares for overland maps, but it’s perfectly fine to use squares for your homemade regional map.

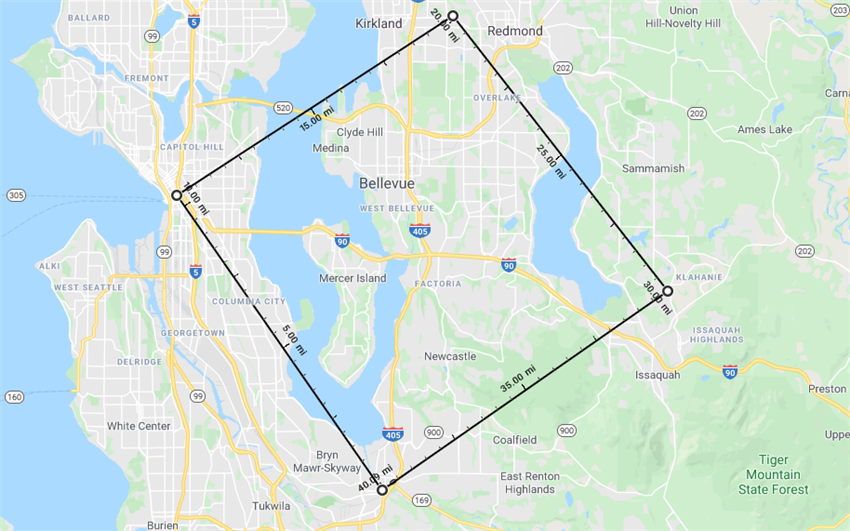

Each one of these squares is one square mile, giving you a 100-square mile area of land. Are you having a hard time imagining how much could land is in a 100 square miles? Try using Google Maps to give you a point of reference, using the Measure Distance feature. For example, 10 miles is about the distance from Wizards of the Coast headquarters in Renton, WA to downtown Seattle, WA. Creating a square of ten miles on each side creates an area roughly the size of the entire “east side,” and a good chunk of both Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish. Try this out in your home state or home country!

A party of adventurers on foot or on horses can travel about 24 miles per day, moving at a normal pace over the course of 8 hours. That means if their home base is in roughly the center of this 10 mile-by-10 mile square, they can journey to any point on the map, go adventuring, and return to the home base in the course of a single day. This is great for episodic adventures as new players get used to playing D&D.

If you want more advice on how to create a province-sized map for your D&D campaign, check out the Mapping Your Campaign section in chapter 1 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Now that you have a local map, you can start filling it with geography. Consider what type of biome your town is in—forested, hilly, mountainous, desert, river land, lakeside, ocean-side, underground, and so on—and extend that biome to the rest of your map. You can add one or two intrusions of other landscapes without things feeling too jumbled or random, but keep it limited. Lakes, forests, and mountains go well together, but add a desert into the mix and your map will begin to feel overstuffed.

If you feel comfortable just drawing on your map, feel free to artistically represent the landscape. Alternatively, you could create a symbol for each biome, like a tree for forests, three wavy lines for a river, three lumps for hills, and so on. Place that symbol inside individual squares to show that square mile is filled with trees or has a river passing through it, and so on. Any square with no symbol is filled with grasslands, snowfields, desert sand, or whatever “basic” terrain type you think is appropriate for your region.

With your geographical local map created, you can now create points of interest, just like you did for your settlement. The wilderness needs different kinds of things for the adventurers to interact with than a town. Start by drawing a symbol that represents the settlement somewhere in the center of the map. Here are four types of locations that every wilderness map should have.

- Village

- Town

- Abandoned settlement

- Mysterious location

- Dungeon

A village is a small settlement of no more than 1,000 people. A 100-square mile area is large enough to support up to six villages of subsistence farmers, and one town of up to 6,000 people. A village tends to be ruled by an elder or some other sort of traditional leader, and a town may have its own mayor or even a minor noble as its ruler. Your campaign may start using a village as a home base, and then move to the nearby town once the adventurers start becoming powerful and renowned. Villages tend not to sell expensive adventuring gear worth 3 gp or more, so adventurers will eventually gravitate towards a town. Most villages send a representative to the town every week or so to sell goods.

A village is a relatively safe location, but monstrous raiders tend to attack them since they aren’t as well-defended as towns. That makes them good places for low-level adventurers to find mercenary work, but a safe night’s rest isn’t guaranteed.

An abandoned settlement is some place that used to be inhabited, but isn’t anymore—perhaps because of war, plague, or a more mysterious cause. Abandoned fortresses, villages, campsites are all places where adventurers can take shelter for the night, or they can be locations for adventure. Abandoned places may be haunted, or they may have been turned into camps for bandits of any humanoid race or lairs for minor monsters like ankhegs, giant spiders, or rust monsters. There may be five or six abandoned locations dotted across your 10-mile-zone map. These monsters will feel more natural if they're native inhabitants of the biome you've created. There's a list of Monsters by Environment in appendix B of the Dungeon Master's Guide. Be careful to choose monsters that are appropriate for your party's level—you can use the D&D Beyond Encounter Builder to make sure your encounters aren't too tough or too easy.

A mysterious location is a place that defies understanding. When the characters find this location, they may ask themselves, “What is this?” or “Why is this here?” An ancient, rune-etched obelisk is a mysterious location, as is a lake that runs red with blood on the full moon, or a waterfall that flows up a cliff. You may want to create a specific reason for this mysterious location to do what it does, or it could just be an oddity of your campaign setting that you’ll give meaning to later. Villagers can let the characters know about these places by telling them rumors or local legends about these places. A map can have anywhere from one mysterious location to one per settlement.

A dungeon is more than just a simple bandit camp or monster lair. For one, a dungeon is large, composed of at least five interconnected rooms. Moreover, something big and powerful resides here, like a young green dragon, or an ettin, and it has plenty of minions and traps filling the rooms of its lair. See the Dungeons section in chapter 5 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide for more information on creating dungeons. Only include one dungeon in your 10-mile zone—it’s something for the players to aspire towards clearing, and they may even make multiple incursions into the dungeon as they explore the region, going back in and out as they gain levels.

If you want more advice on how to fill your province-sized map with interesting locations, check out the Mapping a Wilderness section in chapter 5 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Going Larger

A map of this size can easily fill ten sessions of gameplay with adventure, depending on your interests, and those of your players. Eventually, however, your players will want to explore the world beyond their backyard, so to speak. This is when you can scale your map up to a kingdom scale 100-mile diameter map, with your original map being a single 10-mile square in the larger map. And once they gain an interest beyond your kingdom scale map, zoom out once more to a 1000-mile diameter continent scale map.

Learning how to make a map at that scale are far beyond the scope of this discussion, but they’re important! The Dungeon Master’s Guide is your best friend when it comes to worldbuilding, and reading that book will transform the quality of your campaign.

Have you created a province-scale map? Show us your maps in the comments below!

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus, and the Critical Role Explorer's Guide to Wildemount, a member of the Guild Adepts, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and other RPG companies. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his fiancée Hannah and their animal companions Mei and Marzipan. You can find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus, and the Critical Role Explorer's Guide to Wildemount, a member of the Guild Adepts, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and other RPG companies. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his fiancée Hannah and their animal companions Mei and Marzipan. You can find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020First up: The Forgotten realms was a TSR product in the mid 80s - Ed Greenwood was using it for his personal campaigns earlier than that. I get your point.

Forgotten Realms and Greyhawk have been the two cornerstone setttings for AD&D for over 40 years collectively; which means there is a lot of 'lore' out there as well as baggage.

For the neophyte DM deciding upon whether to create a unique environment or to use a pre-packaged one, the choice is hard. Players don't care much where they're situated, as long as they get to smash enemies, collect treasure, and the PC can be whatever race and class tickles their fancy.

In order to save time and hair pulling, I have several first steps that are useful in addition to the earlier points.

Step 1: Start somewhere familiar. Think of the Prancing Pony at Bree (Middle Earth), that's a great place to start a meet and greet with the PCs. Most PCs are wanderers and/or travellers, a single encounter that brings them together is a good thing. (Inspriation ideas: Seven Samurai, Silverado). Have one or two know each other, and create a loose tether to another character, and away you go.

Step 2: Research. Populations were lower 'back in the day' meaning hamlets were 100 to 400 people, towns villages were less than 1,000, and major cities and towns were 10,000 + (but rarely over 50,000). With a good road and regular breaks, a PC can travel up to 30 miles per day walking. Inns were not always inns, sometimes they were large houses with rooms to let for a night. Hamlets of at least 100 people or so were often dotted across the country side. A small hamlet was usually about 10 to 15 Farms, a market, a smithy, and it's not unreasonable for the mayor, judge, and sheriff were all the same person. Town layouts were almost identical in the early stages, and aside from the odd trail/track to the less used areas, most of the streets would be cart and wagon ready. (We often hear the lamentations of characters in film and literature about small towns looking the same - here's the reason).

Step 3: Populate it. Have a name generator handy with about 20 names each of males and females. Those random NPCs that players will bump into, it doesn't matter if you have a repetition of names (how many Johns, Jacks, James' are there?). Special NPCs, of course have their own profiles, but for those less special (to begin with) less effort is required. Until something happens that makes the nameless NPC special (my players - as they had run out f money and offered to collect outstanding debts for the merchant - accidentally turned the local merchant into the godfather of crime in the town). This is what happens when players are let loose on the world.

Step 4: Trouble and strife. Have a small list of about a dozen minor things that can ail a small community from an ankheg disrupting farms to packs of wolves attacking sheep, the occasional fires, and other bits that the PCs can get involved with. You don't have to have many, but there's always a chance that something interesting could be worked from it (a couple of fires, accident or design?), not all monsters are in dungeons or forests.

Step 5: Reputation. I also like to keep a tally of what the players have done. Eventually, someone wants to shake their hands as they walk down the street for performing that deed (that they may not have done). (I once had some NPCs imitate and convince everyone they were the PCs in order to get free room and board, and then the PCs found these imposters had left bar tabs across several taverns in the city).

Step 6: Don't sweat it. Have fun and let the PCs explore your world, if they go into a forest and you hadn't planned for it, don't worry. Just follow your instincts and improvise. It's your world, do whatever you want you can't be wrong. :)

Being a DM is a challenging job, and the Players will always try to get away with all sorts of shenanigans, and remember: No matter how big a fish they think they are, there's always a bigger fish.

Always remember the most important rule: Have fun.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020Superb stuff!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020I followed this guide and made this map :) Great article!

https://inkarnate.com/maps/lKp7zZRvVey2d6bjP5E1D9k0q8zLnqoaYB8wWQJMGgNXk4r0/MTU4NzEzMzc2ODIxNw==

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020I also like Hexographer, which you can use to randomly generate region maps. It might give you something to be inspired by.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020A really important question, who lives on mercer island

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020I definitely agree that you should start small. But if you are doing a homebrew world and you're playing multiple campaigns in a world or your campaign is going up to higher levels, I would definitely recommend expanding your world! I find one of the most helpful things I have for any session is a detailed world doc that lays out each country and city and what they may run into. It took me years to slowly build so no pressure to get that done quickly. But now that I have it any time my party goes off in a direction I didn't expect, or into a part of town I didn't foresee I have NPCs who live in the city who may show up. I know a lot about the city so just who the rivals might be, or what crime organization the pickpocket might work for etc. Just a lot of little details I can pull from at that moment to be ready for when they go off. And whenever you are thrown off and improvising, or have some time make sure to write down all those details and keep adding to the world doc! Don't kill yourself trying to get it all done or anything, but if you spend even a half hour a week on it you'll have it really nicely fleshed out!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 17, 2020Great article! Many new DMs try to go too big on their first (and second) go at world building!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020Lord Mercer - obviously.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020James, I suspect many new DMs (I have not done this in 30 years until my kids just got interested at Christmas)

have new players who are ending their Phandalin campaigns and Neverwinter is calling to their players.

Big city general tips, or Neverwinter specifics might be a timely topic.

I am imagining how busy you are with DDB BOOMING,

and am in awe of how this stuff is flowing from you in such quantity right now, when needed most.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020I'm on the second adventure of my first campaign (homebrew), and worldbuilding is definitely where I started. For the first adventure, I created a map of an island about the size of South Carolina, which had three kingdoms. Here's the map showing the biomes, farmland, and various cities. The party had to find a cure in Borundria for a plague curse that was ravaging Erdria and Amilex.

The inset in the bottom left was my original world map, but I scrapped that, placing the island into a full-sized world I had previously been playing with. I can't post the map here in case someone I know might see it. XD

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020NICE!

How long did this take you?

What site or software has the hex grid?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020NICE ALEXIUS!

How long di dit take? What site or software has the hex grid?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020Really great of you to do this. You inspire me.

AND valuable content. Thank you Eldar

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020Good article! When you talk about "starting small" and "focusing on details that won’t be important to your campaign for weeks, months, or even years", it may also be useful to reference the "Worldbuilding with Style and Subtlety" and "Worldbuilding through Encounters" articles in addressing how you can still hint at these larger plot/worldbuilding points without necessarily plotting out every single detail of the world that players won't see.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 18, 2020It looks like you mean "diameter," not "radius." I get we're not squaring-the-circle, but a 10x10 grid would be the equivalent of a 5mile "radius" (and a continent sized 1000x1000 grid would be a 500mile "radius."

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 19, 2020Good point!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 20, 2020It can't be a coincidence that WOTC is based next to Mercer Island

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 21, 2020thx!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 21, 2020This is great. Thank you!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 22, 2020Here is a map that I created: (it is a small part of a nation in a continent)

https://inkarnate.com/maps/X48RjQKqBGW01nzNxEaMbmRX6PP9w3loeyJDp25kgVOZrP6d/MTU4NzU2MTcyODY0MQ==