This is the sixth in a series of articles intended to help new Dungeon Masters run great D&D games. In previous articles we've covered how to find a group, how to run your first adventure, how to improve your improvisation skills, what tools you might use, and options for representing monsters on the table.

In this article we're going to dig deep into one of the most challenging aspects of running a D&D game: building combat encounters.

Here's a quick summary of this article's approach towards encounter building:

- Let encounters develop from the story, the situation, and the actions of the characters. We don't have to pre-define encounters as "combat", "roleplaying", or "exploration". We only have to set up the situations and let the players decide how to interact with them.

- Choose the type and number of monsters that make sense given the situation. Sometimes this might be two sleepy guards at a cave entrance. Other times it might be an entire hobgoblin warband. Give the characters openings to take different approaches towards the scene.

- Keep an eye out for unexpectedly deadly encounters. Understand the loose relationship between monster challenge ratings and character levels. Remember that fewer monsters are generally easier than lots of monsters. Use a tool like the tables in Xanathar's Guide to Everything if you're not sure. In particular, be nice to level 1 characters. They're really squishy.

- Adjust the encounter as needed during the game. Vary hit points within the hit-dice range. Increase or decrease damage. Add or remove monsters.

- Mix up encounters to keep things fresh. Add interesting terrain or fantastic features. Throw a mixture of easy and hard encounters at the characters. Use waves of monsters.

We're going to dig into all of these things throughout the article.

Develop Encounters from the Story

Dungeons & Dragons breaks down scenes into three different types of gameplay: NPC interaction and roleplaying, exploration, and combat. In the vernacular of D&D, all of these types of scenes are considered "encounters".

We don’t have to define any scene as being a roleplay scene, an exploration scene, or a combat scene ahead of time. Instead, we can set up the situation and let the players choose how to approach it. Maybe they attack the bugbear leader of the goblins directly. Maybe they try to bargain with them. Maybe they sneak up the garbage chute and try to listen in to the bugbear’s plans. We don’t necessarily know what choices the players will make when they leap into an encounter and not knowing is half the fun.

It’s common to break up our game into a set number of roleplay encounters, exploration encounters, and combat encounters but consider setting those categories aside and simply developing situations. These situations have interesting things going on in them that the characters can get involved with, but we don’t have to know how they will interact with it. Sure, some scenes lean one way or another. When a horde of goblins attacks a wagon filled with friendly farming families (FFFs), the player characters are not going to go investigate rocks. Many times, however, we DMs can simply set the stage and let the players act within the scene as they want. That’s a big part of the fun of D&D.

Choose Monsters that Fit the Situation

As we described earlier, the story and situation drives what encounters takes place. The same is true when we select monsters. Choose the monsters that fit the situation. A hobgoblin war camp might realistically have twenty-five hobgoblins and fifty goblins in it. They might not all charge the characters at once but that’s the size of the war camp. A single hobgoblin patrol might consist of six hobgoblins and a captain. A war party might consist of twenty goblins, twelve hobgoblins, two hobgoblin captains, and a hobgoblin warlord.

We don’t try to balance this war camp with the characters. This is the size of the war camp, the patrol, and the war party regardless of the characters. How the characters decide to deal with a small patrol or approach the war party is up to them.

Sometimes the characters might corner off two hobgoblins who went to examine an old dwarven statue. Other times the characters might find themselves overwhelmed with two dozen hobgoblins and two captains riding on scarred worgs. The story drives the encounter.

Determining Deadly Encounters

Most DMs want to have a vague idea of how difficult an encounter will be. A group of level 17 characters won’t have much of a problem blowing this war camp off the face of Faerun but a group of level 4 characters running up against an entire war party at once could be deadly.

Before an encounter turns to combat, it helps if we know it’s rough potential difficulty. Doing so helps us steer the situation and offer other options to the players before it becomes a surprise total-party-kill (TPKs). Understanding encounter difficulty is tricky and can cause real problems for new DMs. Most commonly, a new DM will pit the characters against monsters that are way too hard and inadvertently kill the characters.

Accidental TPKs are much more likely to happen at level 1 than any other level in D&D. Anyone who thinks a battle between a group of level 18 characters against Tiamat will be rough hasn’t seen what happens when level 1 characters fight too many rat swarms.

Above all else, be gentle with level 1 characters. However squishy you think they are, they’re squishier. If you want to throw some monsters at your level 1 characters, choose fewer monsters than characters (maybe one for every two characters) and make sure they have a challenge of ¼ or less. Even two or three challenge ½ thugs can wipe the floor with level 1 characters. Be nice to these poor young adventurers and you’ll have 19 more levels of delightful pain to inflict.

The Dungeon Master’s Guide has detailed instructions for building encounters at various difficulties. These are the guidelines that Wizards of the Coast themselves use to design monsters and balance combat encounters. I suggest that you ignore these guidelines. They’re too complicated, take a lot of time, and don’t usually give us the results we’re after anyway.

In a wonderful episode of Dragon Talk, lead D&D Designer and rules sage Jeremy Crawford goes into detail on these rules and explains that the main goal isn’t to “balance” encounters but to help DMs gauge the difficulty of a combat encounter, particularly if it’s deadly. The math in the Dungeon Master’s Guide can give us this rough gauge but so can a number of other easier methods. I’m going to offer three different methods for determining whether an encounter is deadly or not and you are free to choose the method you like the best. All of these methods use the same underlying math of the Dungeon Master’s Guide but are easier to use.

First, Xanathar’s Guide to Everything includes a much-improved set of guidelines and tables for determining encounter difficulty. Instead of attempting to calculate encounter balance based on experience budgets, difficulty, and the number of monsters, Xanathar’s Guide includes charts we can reference to determine the equivalent number of monsters to characters at a given character level and monster challenge rating.

Second, I’ll offer some rules-of-thumb you can keep in your head to give you a rough idea of whether an encounter is deadly or not. This takes a little work to memorize but once it’s wired into your head, you’ll need no other tool or chart to gauge an encounter’s difficulty. This method compares the challenge rating of monsters to the levels of characters.

Comparing Challenge Rating to Character Level

It’s important that we understand what the challenge rating of a monster represents. According to the Monster Manual, a group of four characters should be able to defeat a monster with a challenge rating equal to the level of the characters. Thus, a group of level 2 characters should be able to defeat a challenge 2 ogre.

If we reverse-engineer the encounter building math used in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, we can figure out a few other relationships between challenge rating and character level. These comparisons assume a fight that is not quite deadly, but close.

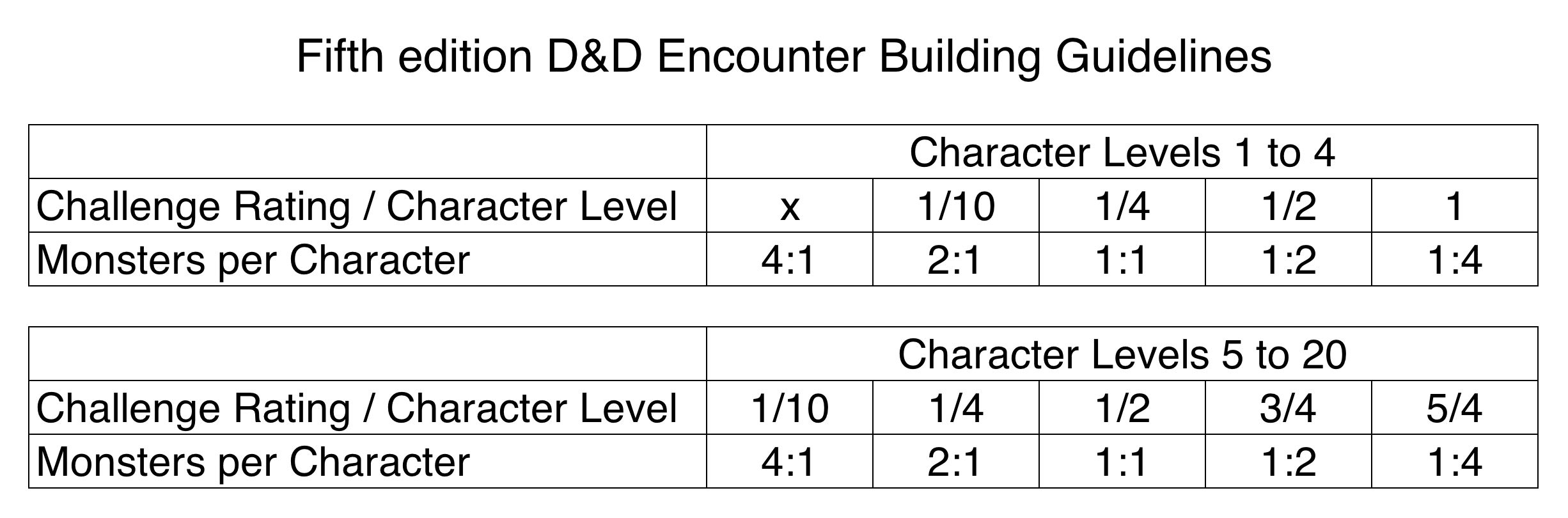

A single monster is roughly equal in power to a single character if its challenge rating is roughly 1/4 of the character’s level. This increases to 1/2 if the character is above level 4.

A single monster is roughly equal in power to two characters if its challenge rating is 1/2 of the character’s level. This increases to 3/4 if the character is above level 4.

Two monsters are roughly equal in power to a single character if the monsters’ challenge rating is roughly equal to 1/10 of the character’s level. This increases to 1/4 if the character is above level 4.

Here’s a small table that might help. The first row is the ratio of challenge rating and character level. The second row is the number of monsters compared to the number of characters.

Any encounters above these amounts, in the quantity of monsters and the challenge ratings of monsters compared to the level of the characters, will be potentially deadly.

This system can't give you a perfectly accurate view of how a battle will go, however. Too many variables determine the difficulty of a combat encounter. These variables include the experience of the players, the synergy of the character classes, how many battles the characters have already encountered, what spells the characters have, what magic items the characters have, the environment they’re fighting in, and, of course, the roll of the dice.

Thus, any guidelines you decide to use to help you understand encounter difficulty won’t be perfectly accurate. Instead, you’ll have to judge for yourself by seeing how the characters fair against various types of fights throughout an adventure or a campaign. Sometimes you’ll need to ease back and make battles easier. Other times you’ll need to increase the number of monsters to challenge the characters.

The more experience you get under your belt running combat in D&D and the better you understand the capabilities of the characters, the easier it becomes to see what the characters can handle and adjust accordingly.

Adjusting Encounter Difficulty on the Fly

There’s a dirty secret among DMs. We’re all cheats and liars. We do, however, cheat and lie for the fun of the game and the enjoyment of the players. We can, for example, vary the hit points of a monster depending on how the battle is going. If the battle is becoming a slog or is simply too hard, we can reduce the number of hit points a monster has. If the characters are carving through monsters too easily, we might increase them to add to the challenge. As long as we’re varying hit points within the hit dice range of a monster, we’re technically not cheating.

For example, an ogre has an average of 59 hit points and its hit dice are 7d10 + 21. Thus, any ogre could have between 28 and 91 hit points. A bigger brute might have 90 hit points but the weaker ones might only have 40. We don’t have to make these changes ahead of time. We can change their hit points during the battle to keep up the high energy pace of the game.

We can likewise tweak the damage of a monster. Like hit points, we’re given an average amount of damage and a damage equation. If we want, we can increase the damage the monster inflicts up to the maximum of that dice range and still be within the rules. Likewise, a hit might be less if we find that the monsters are inflicting way more damage than we expected.

Finally, we can add or remove monsters to tune a fight. Maybe six more hobgoblins rush in when they hear their fellow soldiers being attacked. Maybe two of the hobgoblins flee to get help or become distracted by a third party.

All three of these techniques give us dials we can turn to change the difficulty of a fight while it’s happening. We don’t want to do this sort of thing all the time, but the options are there if things aren’t going well and the game’s fun factor is dropping.

Add Interesting Terrain and Fantastic Features

Six hobgoblins in an open field isn’t that interesting. Four hobgoblins and their four worg mounts camping out around an ancient dwarven archway is more interesting, particularly if that archway is swirling with eldritch energy.

When we’re developing the scenes in our adventure, we can add texture by throwing in interesting terrain or fantastic features. Chapter 5 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide includes two tables of monuments and weird locales we can use as inspiration for some fantastic features to include in our combat encounters. Appendix A of the Dungeon Master’s Guide also includes similar tables for dungeon features. Describing them can give our players ideas about how to use these features in combat which makes the whole battle more dynamic and exciting.

Features like this add an element of exploration and mystery to our scenes.

Final Thoughts on Building Great Encounters

Building great encounters is a skill, like improvisation, that gets better the more we do it. It’s a skill we can improve on for the rest of our lives. By keeping some general guidelines in mind and experimenting from scene to scene, we can learn what works well, what does not, and what things we want to try out in the future.

About the Author

Mike Shea is a writer, technologist, dungeon master, and author for the website Sly Flourish. Mike has freelanced for Wizards of the Coast, Kobold Press, Pelgrane Press, and Sasquach Games and is the author of the Lazy Dungeon Master, Sly Flourish’s Fantastic Locations, and Sly Flourish’s Fantastic Adventures. Mike lives in Northern Virginia with his wife Michelle and their dire-warg Jebu.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 12, 2018This line of articles has been EXTREMELY helpful thank you!!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 12, 2018I listened to your episode on encounters on DM's Deep Dive. You've got a really awesome grasp on everything DMing and I'm glad you're the one doing these articles.

(I'm biased though. I did read "The Lazy DM" before I read the actual Dungeon Master's Guide.)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 12, 2018Thank you @Kinoztic!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 13, 2018Like this article suggests, good encounters are built. This is why I never use random encounters - all my encounters are planned, though the players don't need to know that.

In addition to all the good advice in the article, here are other things that I think can help encounters:

-Weather - fighting in the sweltering heat, a torrential downpour, a blizzard, or dense fog, makes combat a little more interesting and challenging

-Hazards - more than just interesting terrain, put the characters in a setting that actually poses problems and/or advantages, such as the deck of a tossing ship, or the steep rooftops of a cathedral.

-Creatures with unexpected abilities or magic items - what if one of those orcs uses a potion of giant strength?

-Multiple factions - maybe it's not always a two-sided affair - good guys vs bad guys - but multiple groups vying for the same goal.

-Unexpected allies - if a party is having a hard time you can always bring in some back-up.

-Recognize the instinct for self-preservation in almost all creatures - combat should not always be a slog to the death. Creatures, even those of low intelligence, who see the tide turning against them should do whatever they can to survive, whether it is surrendering, negotiating or running away (and not just when it's down to the last goblin who tries to run but is mowed down by opportunity attacks)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 13, 2018Helpful thanks!

SlyFlourish I have 3 clarifications about your chart.

First, How do you round with your chart?

Say I want 1 monster for 1 level 5 character which is 1/2 of level 5 =~ 2.5. Would you round up or down? CR 2 or CR 3?

Second, how do you increase difficulty with your chart if my PCs are almost OP? Xanathar's guide recommends pretending the party size is 50% larger, but I'm assuming that Xanathars chart is defaulting medium strength and your chart defaults to hard. I just want to make my boss battles really challenging without TPK (sometimes 😀).

Third, what do you do with really low CR monsters for higher level PCs? Are they so low level they just don't count in difficulty? (DMG refers to this). I.e., For my 5 Level 5 characters I want to add skeletons which are CR 1/4. This would would be less than 1/10 of level 5. What ratio would you use?

chart looks great and want to use at the table

thanks!!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 13, 2018@fromshus.

Great ideas!

I do, however, LOVE random encounters because it gives me a chance to "cook dinner at the table". The purpose of some loose guidelines is to let us gauge how hard something will be quickly, like when generating a random encounter. Some of the most fun I've had in Tomb of Annihilation is with random encounters.

@Pawnmower.

First, remember that these are LOOSE guidelines. The whole system is loose so worrying too much about the details won't help.

> First, How do you round with your chart?

> Say I want 1 monster for 1 level 5 character which is 1/2 of level 5 =~ 2.5. Would you round up or down? CR 2 or CR 3?

I'd round normally. If it's 2.5, round to 3 (just like normal math stuff). You can, instead, consider the other factors of your characters. Are they particularly robust? Then round up. Are they a bit rough? Maybe round down. Again, it's a loose gauge, not pure science and math. Go with your gut.

> Second, how do you increase difficulty with your chart if my PCs are almost OP? Xanathar's guide recommends pretending the party size is 50% larger, but I'm assuming that Xanathars chart is defaulting medium strength and your chart defaults to hard. I just want to make my boss battles really challenging without TPK (sometimes 😀).

I wouldn't put too much of a fixed ratio increase in play here. I'd just throw either bigger monsters or more monsters at the group if I thought they could handle it. Again, loose gauge, not hard math.

> Third, what do you do with really low CR monsters for higher level PCs? Are they so low level they just don't count in difficulty? (DMG refers to this). I.e., For my 5 Level 5 characters I want to add skeletons which are CR 1/4. This would would be less than 1/10 of level 5. What ratio would you use?

Lots, man. Lots of skeletons. Lots and lots. They're technically not infinite but what makes sense for the story? Are there 100 there? 1,000? I would concern yourself less with what fits the math of encounter building and more with what fits the story. If it's only twenty skeletons, then it's only twenty and the characters have fun destroying them. If it's the army of skeletons that the Red Wizards of Thay left in the cellars of Dragonspear Castle, that might be a lot more.

I ran a fight against a thousand skeletons before. The characters ran down a hall and threw up a wall of flame. The skeletons melted into a new wall of molten bone (I don't know if that's a thing but it was here). When you get to really low CRs versus really high characters, just use lots of them and use the rules in the DMG for adjudicating combat against a large number of enemies.

Hope that helps!

Mike

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 13, 2018Thanks that helps!!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 15, 2018Thanks for the write-up.

The default for designing combat encounters is Kobold's Fight Club and the 8 seconds I spend on it. Period. A mind shift is needed.

D&D could jump on it by making a simple app for this though is not necessary, not because there are 4 versions of tables to get it, but because other digital tools exist.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 16, 2018"Be nice to level 1 characters. They're really squishy." lol

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jan 9, 2019This article is completly contradictory. "Here's the method used, but its not going to work so you just have to wing it." Is not the answer I am looking for.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 28, 2019I guess a follow-up question is: what makes a monster CR 1? Or CR 10? Or CR 1/4? Are those distinctions covered somewhere? I've seen DMs who will outright just wing making enemies, so, how do you get the feel for what satisfies a monster's challenge rating?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jul 5, 2020Thank you so much!!!

This really helped!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 7, 2021Thank you for this! This is super helpful as I'm just beginning to try DMing.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 15, 2023nice one, very informative, the guidelines were the best part