Designing the Dungeon: Gauntlet vs. Labyrinth

“What a dilemma,” the drow moaned, looking over a blank page of parchment. His quill hovered over the paper, the slight silver glow of magic around it shimmering in the darkness. A drop of ink dripped onto the paper, staining it with a messy blot of black ink. The drow roared and threw his arms up in frustration, magically hurling his quill, parchment, and all of his cartographical supplies into the air. He collapsed back in his throne and pouted as the contents of his desk crashed upon the floor in front of him.

Moments later, the door to the drow’s chamber burst open and a breathless goblin scurried in. “Dark master, what happened? Are you under attack? Have the adventurers snuck in undetected?”

The drow affixed his servant with a withering look. “Nothing so dire, worm. I am simply… Oh!” He looked at the goblin with a sudden appreciation and straightened his slumped posture. “Servant of mine, you are a goblin, no?”

“I, uh, am. My family and I all work as your clerks, dark master, should I gather them?”

“No need, no need at all. Your kind live in mines, do you not? Dark, twisty passages filled with countless dead ends, switchbacks, and trapped to high heaven?”

“My cousins did, but my clan were gauntlet-builders,” the goblin replied. A tone of pride tinged his voice, and he permitted himself to smile. “We made deathtraps to protect our home from adventurers. No tricksy turnbacks or secret doors. We captured big, nasty monsters and made vile traps—then put them all one after another. Kept ‘em out well enough, and we didn’t have to dig all those extra tunnels.”

The drow steeped his fingers and nodded. A wicked grin spread across his face, and raised his right hand. With a flourish, his broken inkpots mended themselves and his scattered papers flew back onto his desk. “My faithful servant, I believe you have given me a delightfully devious idea.”

If you’ve ever read a D&D dungeon, explored a twisting, labyrinthine dungeon in an adventure game like Skyrim or The Legend of Zelda, or fought through a straightforward gauntlet of challenges like in World of Warcraft, then you have some idea of how to create a dungeon. You can create an exciting experience in Dungeons & Dragons with either type of dungeon, but your game will be more fun if you can figure out which kind of dungeon is best for your adventure: Gauntlet or Labyrinth?

Unraveling the Labyrinth

In Greek Mythology, King Minos of Crete bade the legendary artificer Daedalus to create an inescapable maze to contain the minotaur, a monstrous half-man, half-bull creature. Creating literal mazes is considered poor form in Dungeons & Dragons, but creating confusing, labyrinthine structures with branching paths and secret passages is a time-honored D&D tradition! This type of dungeon is probably most common in published D&D adventures, whose authors were paid to craft complex, interwoven adventure areas.

In Greek Mythology, King Minos of Crete bade the legendary artificer Daedalus to create an inescapable maze to contain the minotaur, a monstrous half-man, half-bull creature. Creating literal mazes is considered poor form in Dungeons & Dragons, but creating confusing, labyrinthine structures with branching paths and secret passages is a time-honored D&D tradition! This type of dungeon is probably most common in published D&D adventures, whose authors were paid to craft complex, interwoven adventure areas.

The best Labyrinth dungeons are vast, interconnected spaces that give the adventurers lots of information so that they can make informed decisions about how to explore the dungeon. Take for instance a dungeon that has a colony of troglodytes in one area and an abandoned cave filled with stirges nearby. The troglodytes have set up a sturdy barricade at the entrance to their cavern, but there is a relatively unguarded entrance at the back of the stirge cave. The adventurers now have the choice of attacking the troglodyte cave head-on or fighting a small battle in the stirge cave so that they can sneak into the troglodyte lair from behind and catch them off-guard.

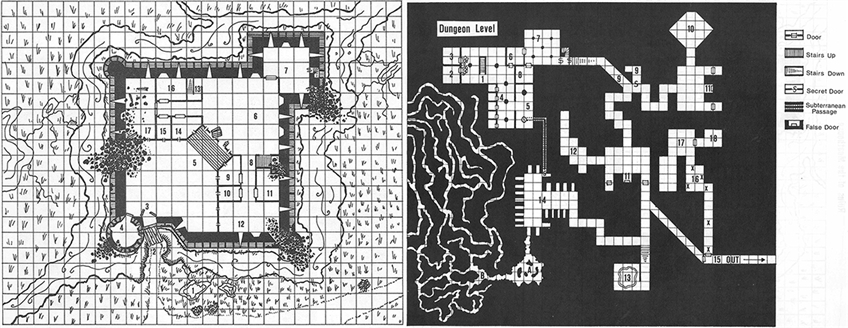

Or, if they wish, the party can ignore the troglodytes and stirges altogether and explore another part of the dungeon entirely! Labyrinth dungeons are all about choice and personal exploration. While most labyrinths are expansive, even smaller dungeons can be labyrinths. Take a look at the map of the Moathouse dungeon from T1 – The Village of Hommlet, by Gary Gygax. The dungeon is rarely interconnected, but there are always choices to be made, even if those choices are as simple as deciding which room to explore next.

The Moathouse, map courtesy of Wizards of the Coast

Why a Labyrinth?

Some people may tell you that labyrinth-style dungeons are the only way to design a dungeon. I disagree. Winding, multi-path dungeons have their uses, but they are hardly the be-all and end-all of dungeon design. A labyrinth dungeon is simply interconnected spaces that the characters must explore, granting the characters more agency but stripping some pacing power from the DM.

Some people may tell you that labyrinth-style dungeons are the only way to design a dungeon. I disagree. Winding, multi-path dungeons have their uses, but they are hardly the be-all and end-all of dungeon design. A labyrinth dungeon is simply interconnected spaces that the characters must explore, granting the characters more agency but stripping some pacing power from the DM.

The greatest benefit of creating a labyrinth dungeon is the level of agency it gives the players. They are the captains of their own ship, and can explore in any direction they want. Whenever you give the players a choice, however, make sure it’s meaningful, otherwise they may as well flip a coin to decide. Choosing between “right door or left door” is meaningless, but choosing between “door covered in leaves of a man-eating plant or door covered in poisonous fungus” is exciting.

Dungeons don’t have to just be filled with fights and traps. Labyrinth-style dungeons are famous for conflict between the different factions of monsters living within its walls. A dungeon may be occupied by both orcs and hobgoblins, but while they both want to kill the player characters, they also want to kill each other and take their territory and loot! Smart players can negotiate with one or more factions in order to make their lives easier as they explore the dungeon.

Labyrinth dungeons allow you to tell emergent stories. Trying to tell a story with tight pacing and a three-act structure in a vast and interconnected space is a fool’s errand. Instead, let go of the pacing, the plot hooks, and the clear-cut objectives, and let your players find their own fun by making foolish decisions, getting sliced up by traps, stumbling upon treasure, and striking deals with greedy hobgoblin generals. If your players would rather skip writing backstories and just want to jump into telling stories through play, you may want to create a labyrinth dungeon.

When is the Right Time for a Labyrinth?

Don’t feel like labyrinth dungeons are a lifestyle. You may find yourself in need of an intricate and winding dungeon in the midst of your story-focused campaigns with lots of pre-planned character beats. If your players are feeling burned out on making realm-changing decisions and dealing with a single major villain, you can direct them to a labyrinth dungeon that gives them lots of small-scale choices and allows them to interact with minor villainous factions. This change of pace could help reinvigorate their interest in your campaign!

Braving the Gauntlet

Running the gauntlet is a form of physical punishment—or even execution, in Roman times!—in which a guilty person must strip naked and run between two lines of soldiers wielding clubs, switches, or blades, and are struck by each soldier in succession. These days, running the gauntlet simply refers to overcoming an intense, straightforward trial. Here, a gauntlet-style dungeon is a linear experience in which characters have little room to explore, but are faced with challenge after challenge until they reap a massive reward at the end.

Some players may find gauntlet dungeons boring, insofar as they are simply funneled along to challenge after challenge, with no personal choice in the matter. Other players are simply here to experience a story and prefer that their choices be tactical ones made in combat, and love that gauntlet dungeons get right to the fun stuff. Most gaming groups have some mix of both types of players, and one of the biggest challenges as a DM is finding how to please both kinds. More on that later.

Why a Gauntlet?

Gauntlet dungeons are straightforward, often linear experiences that test the player characters' combat abilities and their player's puzzle-solving abilities.

Gauntlet dungeons are straightforward, often linear experiences that test the player characters' combat abilities and their player's puzzle-solving abilities.

The greatest benefit of a linear gauntlet is that you can prep efficiently. In a labyrinth dungeon, you may end up only using about half the encounters you prepared, essentially wasting half of your prep time. Either that, or you created all of your encounters as scribbled notes with only a barebones level of prep, increasing the amount of improvising you had to do at the table. In a gauntlet, you know exactly what encounters your players will face and in exactly what order. This means that you can dedicate your time to creating complex, tactical encounters that will reward your players for understanding the ins and outs of their characters’ combat abilities.

Gauntlet dungeons also make it easy for you to tell a story with your dungeon. If your players can only explore a dungeon in a specific direction, you can control how they experience the dungeon’s story. In a labyrinth dungeon, the players may wander from room to room getting snippets of a story, but in a gauntlet you can carefully portion out information, build tension, and deliver plot twists at crucial moments.

When is the Right Time for a Gauntlet?

Ultimately, some players revile linear dungeon experiences because of how they take away player agency. The word railroading is thrown about as a way to revile linear gameplay. Their opinions are their own. If you want to tell a straightforward story and your players are okay with being along for the ride, drop in a gauntlet of challenging fights and puzzles. Just remember that variety is the spice of life.

A Mixed Style

Generally speaking, no dungeon is a pure gauntlet or a pure labyrinth. Like most everything else in the world, nothing is actually black and white—all perceived binaries exist on a spectrum. Most of the dungeons I design, whether for my home group or for publication, fall somewhere in this spectrum of straightforward to complex. A hybrid design works for me because it lets me tell a story with each dungeon like I could in a linear gauntlet, while still maintaining that exploratory feel of a labyrinthine dungeon, even if it is sometimes all just smoke and mirrors.

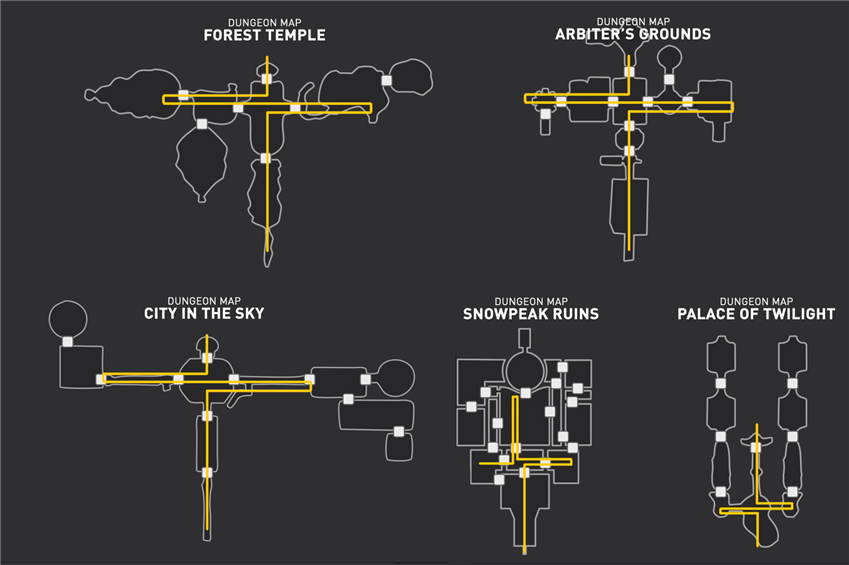

One structure I like to use in dungeons I create for my home games was nicked directly from The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess—though I really lifted it from Mark Brown's superb analysis of the game’s levels in “Boss Keys,” his remarkable series of essays on dungeon design in the Legend of Zelda franchise.

Mark noticed that nearly all of Twilight Princess’s dungeons are characterized by a simple pattern of exploration. Upon entering the dungeon, you face a short challenge and then find a hub room with three main exits. All but one of these exits are blocked off by some barrier, so you take the door that is accessible and explore one wing of the dungeon. Then, you accomplish a goal that unlocks another wing of the dungeon, so you return to the hub room and go into the next wing, accomplish a goal there to unlock the third and final wing, and explore through the third wing until you reach the boss.

Screenshots courtesy of Mark Brown

Most of the dungeons use this exact “hub, east, hub, west, hub, boss” structure—and even those that don’t still see the player returning to a hub room three times before fighting the boss. In Mark’s words, “it didn’t immediately impact my enjoyment of the game back [when it launched], but it does perhaps explain why all the dungeons feel a bit unremarkable.”

Mark was critical of Twilight Princess’s dungeons in his analysis, but don’t let this scare you off from using this spectacular dungeon layout. But this isn’t the fault of the dungeon structure; rather it’s the fault of the game’s overreliance on it. This structure is actually remarkably clever. Mark himself said “On its own merits, [this repeated structure] is actually pretty good. […] For one, it splits the dungeon into small chunks that can be accomplished in isolation. […] This structure also keeps the player focused on their long-term goal in the central room. […] And by repeatedly bringing the player back to that previously explored room, it feels less linear than just putting the chunks in a big row, one after another, which is effectively how you’re going to play them.”

There’s a lot of good advice for D&D dungeon builders to unpack here. First of all, this hub-room structure allows you to break your dungeon up into sections for the players to explore at will. Breaking your dungeon up into bite-sized chunks sidesteps the greatest downfall of the labyrinth-style of dungeon: its broken pacing. By creating a central hub chamber and allowing your dungeon to be explored one wing at a time, you can tailor each wing to fit a single game session. (Maybe each wing is its own Five Room Dungeon, like we talked about in the first Designing the Dungeon article?) This lets each game session have its own mini-arc, with the players feeling like they’ve overcome a great challenge and actually managed to accomplish something at the end of each wing.

There’s a lot of good advice for D&D dungeon builders to unpack here. First of all, this hub-room structure allows you to break your dungeon up into sections for the players to explore at will. Breaking your dungeon up into bite-sized chunks sidesteps the greatest downfall of the labyrinth-style of dungeon: its broken pacing. By creating a central hub chamber and allowing your dungeon to be explored one wing at a time, you can tailor each wing to fit a single game session. (Maybe each wing is its own Five Room Dungeon, like we talked about in the first Designing the Dungeon article?) This lets each game session have its own mini-arc, with the players feeling like they’ve overcome a great challenge and actually managed to accomplish something at the end of each wing.

Returning to the hub room allows you to give the players a sense of the progress their characters have made. This can be a difficult line to walk. If you’re too obvious about it, the whole venture can feel very artificial and video-gamey. Putting a giant iron door in your hub room with three keyholes that can only be locked by three magic keys that are each guarded by a mini-boss in the three wings of your dungeon… that feels bad. But if the players are raiding an orc army camp and can see the growing effects of flooding their foundry, then burning their barracks, then exploding their shipyard? That creates excitement.

Most importantly, this knotted structure allows you to create a labyrinth out of tiny gauntlets. This is actually in contrast with the dungeons of Twilight Princess, which are complex structures made simple by locking you out of all paths but the critical path. We don’t have to go that far. Tricking your players by offering them an expansive experience and then revealing it to be a linear artifice is just poor sportsmanship. Instead, I recommend allowing your players to tackle any wing of the dungeon they want to in any order, save for the boss wing—which must be tackled last. This lets your players choose which challenges they want to tackle, but still lets you conserve prep work by only creating challenges that you’re sure they will face.

Season to Taste

I conclude this article with my usual word of warning for Dungeon Masters. I’ve given you a few extreme examples to help guide your design, and then tempered those extremes with my preferred style. I love the way I design dungeons, and it works great for my gaming group. I put thought and consideration into how I structure them so that they engage my players and still serve my story-first style of gameplay.

I conclude this article with my usual word of warning for Dungeon Masters. I’ve given you a few extreme examples to help guide your design, and then tempered those extremes with my preferred style. I love the way I design dungeons, and it works great for my gaming group. I put thought and consideration into how I structure them so that they engage my players and still serve my story-first style of gameplay.

But you’re not me. If you like my style, please steal it. I’d be flattered. But the point of this article isn’t to argue that one style of dungeon is better than another, or that you’re a more valid D&D player for exploring dungeons instead of fighting straight through them. Identify your favorite dungeons in games you love, both video games and tabletop games alike. Figure out why you like them, and put that same level of thought and enthusiasm into creating a dungeon for your players.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of the Critical Role Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and Kobold Press. He lives in a five-room apartment/dungeon in Seattle, Washington with his partner Hannah and his two furry goblins, Mei and Marzipan. You can usually find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of the Critical Role Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and Kobold Press. He lives in a five-room apartment/dungeon in Seattle, Washington with his partner Hannah and his two furry goblins, Mei and Marzipan. You can usually find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 7, 2018A great article, James. Thanks!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 7, 2018Love these articles. The team should tag the posts so if I want to, say, read all the 'Designing the Dungeon' or 'Class 101' posts I can find them easily.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 7, 2018Is it just me or is the beginning story with the drow and the goblin designing the ultimate dungeon the best part of these articles?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 7, 2018Goods advises and i like the reference with Zelda

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 7, 2018Excellent article! I'd like to echo the tagging, though I believe a prior article's comments already mentioned this would be done (Though I could be wrong.) Hope many more of articles of this quality are to come!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2018Another great article James, your recent articles has been eye-opener for me

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2018Between these and Mike Shea's articles, I think I like this content better than the actual DDB tools offered.

A year or two ago I made a dungeon for my players that still stands out with them today. While reading this I realised I unknowingly built a Zelda Boss Keys dungeon and as mentioned it really worked.

I started out with a big plus as a central hub: 4 exits, one of them being a large stone door with a face etched on it. The face spoke only in rhymes and told the players they needed to overcome three challenges lest the door remained closed.

Each exit had it's own little gauntlet though in riddle form. One had a fully working and stocked blacksmith's workshop where they had to craft something so fragile that the mere mentioning of it would destroy it. The workshop was designed to mislead as the answer was 'silence'. The party got it by casting Silence over the workshop's roaring fire.

The other one involved perseverance, where the party had to hold down a button while by doing so they unleashed more and more dangers into the room, including the walls closing in.

The third exit led outside to a beach with a shipwreck. A lone skeleton lay on the ground with one hand streched out as if waiting for a gift. Random items from the ship were scattered about - like a stone apple, a compass, an empty watet flask, etc - and the party had but one chance to choose. They failed this one and it seemed like their chance of opening the door and escaping the dungeon was gone. ( I honestly can't remember what the solution was).

The party decided to try and trick the Stone Face by forging a fake key in the workshop. The Door quickly saw through their ruse and punished them for cheating the game by literally pulling the rug from under them, dropping the party into a literal maze below. A maze with a time limit, every 2 hours they would receive 1 level of exhaustion on a failed save. Meanwhile, mazedwellers would torment them while trying to navigate.

To make the maze feel more like an actual maze to the players I removed the flipmat and only asked them if they wanted to go left, right or straight at each intersection. This proved challenging to the party as they had trouble with the fact that 'right' would become 'left' after turning around at a dead end.

Many curses towards the maze, me, and ultimately eachother ("whose idea was it to fake a key anyway!") and one KO'd by exhaustion player later, they found the exit - a false wall they passed multiple times, obviously.

Two years and many sessions later this dungeon still comes up during play. Whatever hurdle they encounter, "at least we're not in that maze again!".

I chalk it up as a success :)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2018I dig it. I love Mark Brown's videos and boss keys is extra awesome. You should also check out "Extra Credits: Durlag's tower" series. They do an amazing job breaking down the different components of that dungeon.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLDPL7seU9mMcBZ8yonxZvyEcFHg8dy1wl

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2018I tend to wait a little while before offering the adventurers a labyrinth. I like them to be somewhere between Level 3 and Level 5 before they delve into their first dungeon crawl because by then the players have developed a sense for their characters, skills, abilities, and have one or more levels of experience with their subclass feature.

Plus, they can clear out sections without investing a lot of time. They can come back or push through. They can test the dungeon crawl and reassess their supplies. Are they properly equipped for THIS labyrinth. Not all labyrinths are the same. Some required ropes and grappling hooks and the use of a levitation or spider climb spell, or even magical items with similar properties to navigate the crawl better. I have one planned for my group n the next few weeks. Lets see how they fare?

Happ adventuring all!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2018..

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2018How do I upvote this?? And same with the Class 101 series!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2018This was quite interesting -- it really helped open my eyes a bit about how to easily design dungeons and gauntlets. Just knowing whether you're asking 'dungeon or gauntlet' already solves half of the issues with it. I mostly find this interesting because I recently ran my own players through a gauntlet of a single battle. I gave them time to prepare, a free long rest, a level up, and some new shiny tools, and they almost lost anyway! There was a margin of two hit points!

( But then, that's what you get for throwing three level-3 players against seventy goblins seven bugbears four imps and a spined devil with a poison 'supreme healing potion' in their back pocket <Which I REALLY should have predicted would have been used at the last second, my bad, live and learn> )

I admit I didn't even think of having a similar experience as a series of separate battles, though I probably should have. Have you considered writing a guide on how to make different ways to make combat interesting and challenging? Single combat encounters, I mean, ones that will really stick out in the players memory. That's just the the challenging fight before the fight against the boss, which will be challenging in a -- different way. I do mean things like single battles, and not a full-on dungeon.

I can think of a few, but I'm very inexperienced, and I would love a new way to frame it in my head. Have the enemy in an obviously tactically advantageous position, such as bows and arrows behind makeshift palisades. Having enemies in obviously Disadvantageous positions. Have them be hunted in a maze where they can't tell what's going on, but the enemies know where they are, so they can't rest. Have them face off against an army, and need to find ways to block off ways the enemies can get inside so they can take them down one by one. Make it so they have to Stop The Bad Thing, or Attack The Bad Guy, but they can't do both in a single turn. Things like that, for epic encounters, besides just plopping down a Beholder or a Dragon in their way?

Not that one shouldn't use Beholders or Dragons.

Obviously one should.

But variety is the spice of life.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2018Very insightful! Perfect timing too! Resumes inking out a most devious dungeon for the party.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2018As a player, it was a druid throwing a flying potion at a barbian at level 2... The (flying, ranged) flaming skull didn't live much longer after that.

As a DM, it was the warlock dominating person on the boss and having him kill the goonies while the group built up defenses (literally dug a trench, cast spike growth, the whole nine yards) to fight against the boss (who they were supposed to be too weak to fight and needed to run from).

It's hard to "make" an encounter special... it's more about making the story fit, and letting the dice do the work for you...

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2018I have always been a fan of the multiple room, multiple path approach to dungeons. I prefer though to have the access "keys" not in a logical sequence, forcing the party to not only figure out what they need but also what needs to go where. Excellent article.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 11, 2018I have been replaying one of my favorite RPGs, Fallout: New Vegas I have found the game to be the epitome of what to do and what not to do when designing dungeons.

What do:

What not to do:

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 11, 2018new to D&d thanks for the info

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 25, 2018I like the mix style... It makes the players have more skin in the game.