Spell Spotlight: Conjure Animals

“I cast conjure animals!” declared the druid. Magic flashed in his eyes, and eight snarling wolves appeared around him, their fur shimmering with fey magic.

“Oh hell,” groaned the Dungeon Master. She looked up from her notes at her players, and she suddenly seemed very tired. “Time out, team. I need to go through a few books. Paul, do you need a Monster Manual?”

“No, I uh,” the druid’s player glanced up from his Player’s Handbook as he frantically flipped through the appendices. “I think I’ve got it. I just need to, uh, roll initiative, I think.”

The fighter’s player looked at her DM and grimaced apologetically. “I’m gonna go to the bathroom, is that cool?”

So you cast conjure animals, or one of your players did, and now everyone’s stopped in the middle of combat to check the rulebooks. Maybe you’ve summoned eight wolves and now you’re controlling nine different characters in combat, and all of your friends are twiddling their thumbs and waiting for you to stop hogging the spotlight and to let them play some D&D.

This all-too-common situation sucks, but it doesn’t have to be this way. There was a great discussion last week about the role of creature-conjuring spells and the druid class last week in the comments of Druid 101: A Beginner’s Guide to Channeling Nature’s Might. I opted against including conjure animals in my list of recommended spells, which garnered some confusion from optimization-focused readers. It’s true, spells that summon other creatures are incredibly powerful. They’re also extremely newbie-unfriendly, and I didn’t feel comfortable recommending it to new players in a 101-level guide.

But that’s just avoiding the issue. Sooner or later, people are going to pick up conjure animals, conjure minor elementals (which I talked about previously in Spell Spotlight: Conjure Minor Elementals), conjure woodland beings (which is rife for abuse in its own way), or any of the other spells that summon multiple creatures to aid you. And when that happens, both players and DMs alike will need to understand the impact of these spells so they don’t negatively impact their entire group’s play experience.

What’s the Big Deal?

In order to solve the problems with conjure animals and its ilk, we need to understand why this spell creates problems at the table. Conjure animals is a very powerful spell, but that’s by design. 3rd-level spells like fireball are supposed to mark a huge increase in power for their casters. Its problems lie elsewhere.

Certain creature-conjuring spells give the caster a limited choice of what creatures to summon. Conjure animals allows its caster to summon one of the following:

- One CR 2 beast

- Two CR 1 beasts

- Four CR ½ beasts

- Eight CR ¼ beasts

Summoning spells are typically at their most powerful when they summon as many creatures as possible. Action economy is so important in encounter design that often simply being able to perform lots of attacks or other actions is more powerful than making one or two powerful attacks. Even against overwhelming odds, fights in D&D are usually determined by one side outnumbering the other. Summoning 8 wolfs is one of the most optimal uses of the spell, since even though these creatures are individually weak, their Pack Tactics trait grants them advantage on just about every attack, and they can knock enemies prone. Even though the saving throw to resist being knocked prone is only DC 11, even high-level creatures are bound to roll a 1 eventually, and eight chances of knocking your enemy prone per round can really wring the low rolls out of a die.

Summoning spells are typically at their most powerful when they summon as many creatures as possible. Action economy is so important in encounter design that often simply being able to perform lots of attacks or other actions is more powerful than making one or two powerful attacks. Even against overwhelming odds, fights in D&D are usually determined by one side outnumbering the other. Summoning 8 wolfs is one of the most optimal uses of the spell, since even though these creatures are individually weak, their Pack Tactics trait grants them advantage on just about every attack, and they can knock enemies prone. Even though the saving throw to resist being knocked prone is only DC 11, even high-level creatures are bound to roll a 1 eventually, and eight chances of knocking your enemy prone per round can really wring the low rolls out of a die.

The problem—that conjure animals and similar spells dramatically slow down play—manifest in many ways. First, creating lots of monsters creates a long player turn. This in turn causes a social dilemma in which one player hogs the spotlight. Many of the solutions to these former two problems create more work for the DM, disrupting their fun and further slowing down the game. It also creates a headache when fighting in cramped quarters, because beasts crowd the battle map. A fifth issue is that the ease with which this spell is dispelled can render this investment of time a waste. Let’s take a quick look at each of these in turn.

Long Turns and Hogging the Spotlight

When a character casts conjure animals, the summoned creature or creatures roll initiative and get their own turn, and all creatures summoned by that casting of the spell act on the same initiative—essentially giving the caster another turn in combat! However, this second turn has the power to be even longer and more complicated than the caster’s own turn, since as stated above, the most powerful way of using creature-summoning spells is usually to summon as many creatures as possible.

When a character casts conjure animals, the summoned creature or creatures roll initiative and get their own turn, and all creatures summoned by that casting of the spell act on the same initiative—essentially giving the caster another turn in combat! However, this second turn has the power to be even longer and more complicated than the caster’s own turn, since as stated above, the most powerful way of using creature-summoning spells is usually to summon as many creatures as possible.

If a character ends up summoning 8 wolves, that player is now suddenly controlling 9 individual units. Even if the wolves are simple to command, that’s 8 additional movements, 8 additional actions (and possibly 16 extra d20 rolls, thanks to Pack Tactics granting advantage to their attacks), with the DM rolling a Strength saving throw for every successful attack, potentially ballooning that number to a monumental 24 extra d20 rolls made per round thanks to one spell.

The summoner can help mitigate this by planning their turn in advance, but even with all that prepared ahead of time, all that dice rolling will still drag the game to a standstill. By gaining a second turn in combat and making that turn take longer than most other players’, this presents a social problem as well: hogging the spotlight.

Solution (Player): As a player, the easiest way to solve this problem is to just summon a single CR 2 creature instead of a bunch of weak creatures—but this solution might not please everyone. It’s giving up a lot of the spell’s power in exchange for an easier and more fun play experience. If you really want to summon all 8 beasts, you should do everything in your power to make your additional turn go as quickly as possible. Before your conjured creatures’ turn, prepare the following:

- Exactly where each creature goes and what action it will take.

- If it’s performing an action that requires one or more die rolls, such as attacking or making an ability check, make all the rolls in advance. If you’re attacking, roll the d20 to hit and the d4s for damage at once. If you and your DM really trust each other, consider asking to roll the d20 for the creature’ Strength saving throw, too.

If you want to avoid hogging the spotlight, instead of having your summoned beasts act on their own turn, consider asking your fellow players if they want to play as the beasts in addition to their own characters. This house rule lets other players have fun with your spell by letting them play the beasts on their own turns, in addition to their character. This giving them more tactical choice, and spreads the turn time around more evenly than just giving you an extra turn.

Solution (Dungeon Master): As a Dungeon Master, if your druid constantly summons the maximum number of creatures, you could treat those 8 wolves as a mob, rather than individual creatures, in order to reduce the amount of time spent rolling dice. Rules on how to use mobs and make mob attacks are found in Chapter 8 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide. Be sure to talk to your player before changing the rules on them. They expect the game to be played a certain way, and changing that without explanation can be incredibly frustrating.

Overworking the Dungeon Master

Let’s face it: Dungeon Masters have a lot on their plate to think about already. In combat, the DM is playing all the monsters and keeping all of their spells and unique abilities in their head, keeping track of terrain hazards and hidden traps, and perhaps most importantly, keeping track of all of the players’ abilities so that they can tailor challenges to their strengths and weaknesses. The list goes on, of course.

Let’s face it: Dungeon Masters have a lot on their plate to think about already. In combat, the DM is playing all the monsters and keeping all of their spells and unique abilities in their head, keeping track of terrain hazards and hidden traps, and perhaps most importantly, keeping track of all of the players’ abilities so that they can tailor challenges to their strengths and weaknesses. The list goes on, of course.

Here’s something most people don’t know about conjure animals and similar spells: the caster doesn’t get to choose what creatures get summoned. Let me say that once more for the people in the back: the caster doesn't get to choose the exact creatures conjured by their spell. By the text of the spell, the player only chooses the number of creatures summoned and their challenge rating; the DM does all the rest. This is further supported by Jeremy Crawford’s Sage Advice (page 13 of this PDF), in which he says, “The design intent for options like these is that the spellcaster chooses one of [the listed challenge rating options], and then the DM decides what creatures appear that fit the chosen option.”

You may choose to allow players to select exactly which creatures appear, but understand that you’re actively changing the way the spell works. Empowering the DM to choose what creatures appear instead of the player is one of the spell’s balancing factors—but it’s also a big problem for DMs who aren’t prepared to suddenly choose a bunch of creatures. If you’re a DM, can you name any CR ½ beasts without looking them up? More than one? Even if you can, does the caster have the stats, or will you have to hand them your Monster Manual so they can play the four CR ½ crocodiles that just appeared?

Solution: Fortunately, the D&D Beyond Monster Finder makes finding creatures of a specific type and challenge rating quicker and easier than it was with just books. If you know you have a character that has conjure animals or a similar spell prepared, it might be worth it to keep a tab of the Monster Finder open at all times.

Crowding the Battlefield

Putting lots of new miniatures on the board to represent the conjured creatures takes time, but we’ve driven the “conjure animals wastes time” point into the ground by this point. More troublesome is how they make it impossible for anyone to navigate the battlefield.

When fighting in a 10-foot-wide dungeon corridor, summoning eight CR ¼ beasts and winding up with a herd of cows blocking your path is—I admit, very funny—but also a big problem for the DM and for other players. Suddenly, allies and enemies alike are unable to wade through the sea of animals clogging up the battlefield. Remember that space occupied by another creature, even a non-hostile one, counts as difficult terrain!

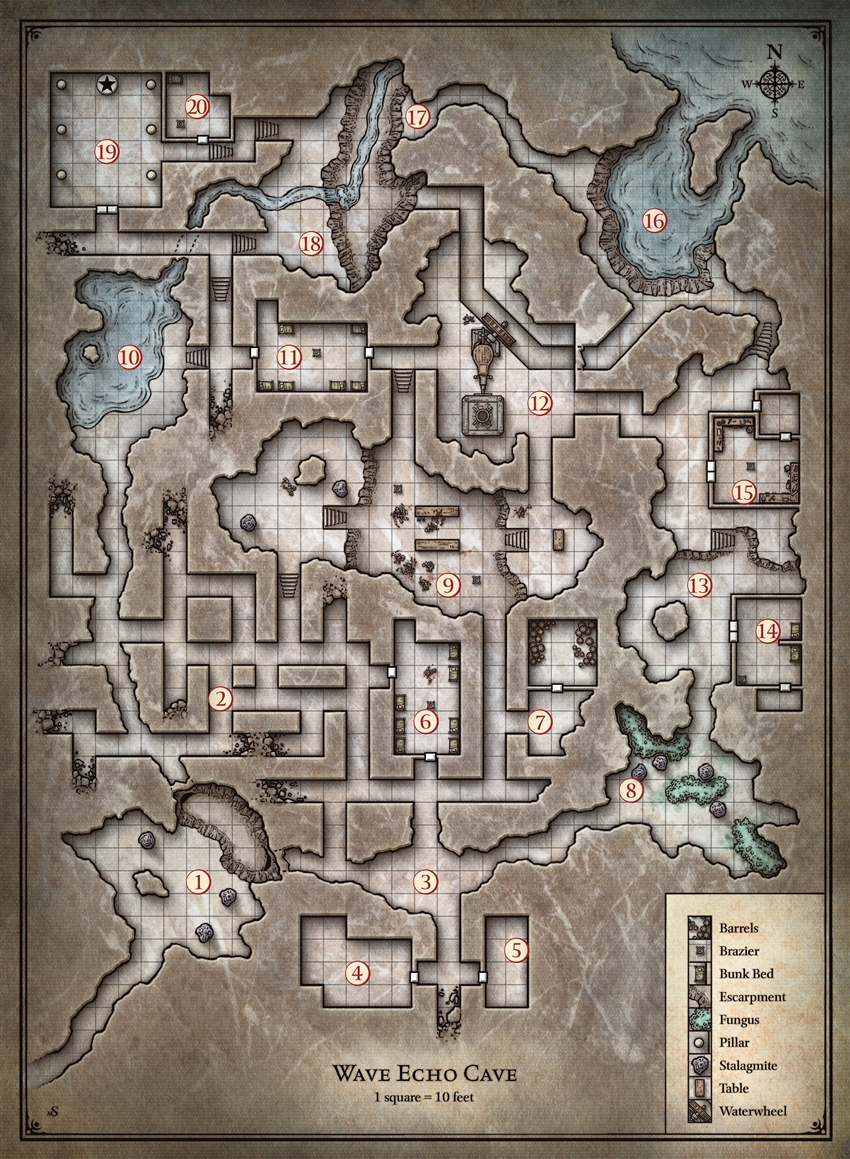

When in a field full of rolling hills, this concern vanishes into smoke. There’s lots of room for everyone to navigate. Consider a middle ground, like Great Cavern in Wave Echo Cave from the D&D Starter Set.

Area 9, the Great Cavern, is already filled with seven ghouls. It’s a fairly spacious cavern, but it’s divided into three sections, two raised platforms on the east and west of a depressed central chamber. All seven ghouls “lurk in the shadows on the western ledge,” and most parties will be walking straight through the central chamber. The battle will very quickly descend into a frantic melee in the middle, as all seven ghouls use their bite and claws to tear into the PCs, essentially removing the spacious east and west ledges from the fight.

Even the central chamber, with its spacious 10-foot squares, would get very crowded very quickly by the sudden appearance of 8 Large-size cows milling about, in addition to the seven ghouls and four-to-six adventurers. At that point, the battlefield becomes cluttered and hard to interpret at a glance, which further slows down combat, and makes it difficult for both heroes and villains to move tactically, thanks to all the opportunity attacks that could be thrown around. Even with the eastern and western wings of this room free of bodies, it doesn’t make sense for either side to retreat there, since the ghouls want to stay in melee, and the characters will have a hard time navigating the sea of non-hostile difficult terrain and hostile opportunity attackers.

Solution: This is a particularly vexing problem for groups that use miniatures and grids to engage in tactical combat. There isn’t an easy solution for it, but it is a point in favor of using Theater of the Mind combat instead of gridded combat. If your gaming group has been having a problem with conjure animals crowding the game board, consider playing a few combats in Theater of the Mind instead of with miniatures.

Alternatively—and this one is a house rule—you could consolidate the conjured animals into a single space as a herd or a pack, not unlike how swarms work in fifth edition D&D. A pack of eight Medium creatures (like wolves) count as a single Huge creature, and fit into a 3x3 space, whereas a swarm of eight Large creatures (like cows) count as a single Gargantuan creature, and fit into a 4x4 space.

This solution doesn’t actually create a swarm, since swarms have a few unique traits and consolidate hit points and attacks in a way that would just make a DM’s life harder when adjudicating gameplay on the fly. Conjured animals in a pack move as one and can surround another creature, but attack individually as usual. This mitigates the problem of the beasts cluttering up the battlefield by putting them in a tidy block, with the slight downside of restricting the granularity of their movement.

Dispelling Conjure Animals

Conjure animals may be extraordinarily powerful and—in some cases—extraordinarily annoying, but it’s actually quite easy to remove these animals from the battlefield in most situations. There are three main ways to counteract the effects of this spell: direct damage, magic removal, and breaking concentration.

Conjure animals may be extraordinarily powerful and—in some cases—extraordinarily annoying, but it’s actually quite easy to remove these animals from the battlefield in most situations. There are three main ways to counteract the effects of this spell: direct damage, magic removal, and breaking concentration.

The most obvious way to deal with the beasts summoned by conjure animals is to just kill them. If the caster summons eight wolves in a clump, a single fireball could easily wipe them all out—though casters can easily fireball-proof their casting by spreading out their conjured creatures. Generally speaking, though, killing the conjured animals one-by-one is the least efficient way of dealing with them.

Magic removal like dispel magic is actually ineffective against conjured creatures. Dispel magic ends ongoing magical effects, but conjure animals is an instantaneous effect that causes one or more creatures to appear. Counterspell can negate the casting of conjure animals in the first place, but it’s still a fairly inefficient route. You’re just trading one of your 3rd-level spell slots for one of theirs.

Breaking the caster’s concentration is the most efficient, but least consistent, method of dealing with conjured creatures. In some cases, the caster may simply wish to use a different spell that requires concentration—and fortunately, the vast majority of druids’ powerful spells do require concentration! If you absolutely have to end their concentration on conjure animals as soon as possible, focusing fire on the druid will do the trick. Even if you’re needling the caster with tiny attacks, they’re bound to fail a DC 10 Constitution saving throw eventually. And as soon as their concentration drops, the spell ends and every single conjured creature disappears instantly!

Tinkering with Troublesome Spells

Most of the advice here applies to other spells that conjure creatures, but they all have their own strengths and weaknesses. Conjure animals gets a lot of bad press because it sits right at a “break point” of power in D&D, the transition between 1st tier and 2nd tier play. This is the point where D&D becomes harder to run for most DMs, since characters begin to acquire more and more powerful and complex powers. With this in mind, the best advice I can give to players and DMs in D&D games with 2nd-tier or stronger characters is to keep practicing and keep playing. The more experience you have and the more you work with your players to improve your game, the more fun you’ll have.

Most of the advice here applies to other spells that conjure creatures, but they all have their own strengths and weaknesses. Conjure animals gets a lot of bad press because it sits right at a “break point” of power in D&D, the transition between 1st tier and 2nd tier play. This is the point where D&D becomes harder to run for most DMs, since characters begin to acquire more and more powerful and complex powers. With this in mind, the best advice I can give to players and DMs in D&D games with 2nd-tier or stronger characters is to keep practicing and keep playing. The more experience you have and the more you work with your players to improve your game, the more fun you’ll have.

And if there’s a part of D&D that isn’t working for you, like one spell that ruins your fun no matter how much you try to make it fit into your game… drop it! The rulebooks are meant to be a toolkit to run the game in a way that helps you and your friends have fun together. There’s nothing inherently virtuous about playing by the book, save for consistency of expectations between gaming groups. If you lay out proposed houserules (like “the spell conjure animals doesn’t exist in my game”) to your fellow players beforehand and they all agree with it, then you’ve successfully created a new expectation for your game and your game alone.

If you’re a game designer (aspiring or established) or an Adventurers League DM, it’s well worth your while to learn exactly how this spell works so that you can design encounters and situations that can withstand this spell—both in terms of its power and its ability to slow down the game. This is a valuable tool to have in your toolbox, and theory can only take you so far. Go out and experience it in play!

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of the Critical Role Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and Kobold Press. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his partner Hannah and his two CR 18 troublemakers, Mei and Marzipan. You can usually find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of the Critical Role Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and Kobold Press. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his partner Hannah and his two CR 18 troublemakers, Mei and Marzipan. You can usually find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018The thought of someone at my table casting this spell scares me... I know this will stop the game for about 10-20 mins.. easy... however after reading this I'll be more prepared as a DM.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018Oh no, please remove the picture of Wave Echo Cave from the post (or at least add a spoiler alert)! I am walking through that campaign right now and my player's are bound to read this!

Excellent article otherwise though!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018That's a very fair request. I've hidden the map behind a spoiler from here on out.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018Good article. I have DM'd for Druids and Necromancers. Having the stats ready and rolling quickly is the key.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018I feel like this article is my fault...

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018You know what modification I would make? Removing the 'verbal command' part. Instead, on each of the caster's turns, as a bonus action, they can decide an action for some number of the summoned creatures. The creatures cannot be commanded to move towards separate areas or creatures, and if they are commanded to make an attack, ALL summoned creatures that are within reach of the target make the SAME attack against ONE target. And since issuing multiple mental commands is hard, each turn that they command the creatures, the caster must make a concentration saving throw, with a DC of 5 + the number of creatures commanded. Or maybe, just a wisdom check, DC of 8+ the number of commanded creatures, to successfully issue the command.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018And I for one am glad it happened. Good point last week, and the follow up post was great.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018I think the main issue with conjure animals is that it puts the burden of preparation on the player unlike anything in the game aside from the other conjure spells. It's on the player to know the kinds of monsters they can summon and their statistics. Once they cast the spell, it's on the player to be pay attention to combat, prepare the attack and damage rolls of the summoned creatures, track their HP and any status effects they might be affected by.

An unprepared player casting the spell and asking the DM "OK, what do I get?" is going to be the kind of problem people dread when they hear horror stories about the spell turning combat into a slog. A prepared player would ideally have the monsters they'd want already in mind, their stats tucked away somewhere with the rest of their character information, and probably a pile of dice they'd use to roll their actions in combat.

To that end, I think that the suggestion of having the DM pick the monsters that the player gets would actually be detrimental. Aside from adding a phase when the spell is cast where the DM has to do extra work picking the monsters, the player would suddenly have to possess the statistics to all the monsters they might potentially summon and would have to potentially use different attack bonuses, special hit effects, armor classes, and hit points, increasing the complexity of an already complicated spell.

Unrelated to the mechanical play of the spell, conjured animals as per the spell description, have a duration of "Concentration, up to 1 hour" and not "Intstantaneous." I could be mistaken, but I believe that the question of how Dispel Magic interacts with conjured animals is if it dispels all of the conjured animals with a single cast or just one of the conjured animals.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018The way we handle it is that I (the druid) typically use the same one or two beasts. They work as a group. We have made it so I roll to hit on all of them at the same time (I usually roll before it's their turn) and then roll all damage at once. The DM calculates when one creature dies and then just moves on to the next. It really doesn't take that long ... no longer than someone rolling for several hits with multiple damage dice.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018I'm planning a druid in my current game, and I'm trying to help my DM through the "what do I get?" paradox by doing the following:

1) I've rolled through the monster listings and drummed up a list of 3-4 creatures per CR level and environment and given it to my GM. This way when I cast the spell, what shows up can be thematic to the environment (something my DM wanted to make happen). This also lets me weed out problematic monster choices (I won't summon more then 2 of anything with pack tactics, that sounds boring even to me) and "whammy prize" monsters (rats, crabs, and other 0 cr monsters that technically satisfy the spell)

2) I've pulled monster stat cards for everything on that table. If you want to use dnd beyond for this mid fight, game on. I'm already keeping it open for my character stuff though and i don't want to hassle with tabs etc. during my turns. Once my DM arrives on a creature, I'm ready to go and don't need to dig out extra stuff.

I like the idea of sharing control of the summons with the party though, I might steal that.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018This is really interesting. I was lucky that my druid player joked about dinosaurs etc. in Ravenloft so we were able to talk about how the spell works.

In my campaign I requested summons fit his background (island born) or character in-game experience.

It was fine from there but the potential friction came from our situation of the group having gamed for years and assuming things are the same in 5e, or the same as we used to play them.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018If you play a Druid or have one at your table as DM, please don't gimp one of the Druid's signature spells in 5e: Learn Those Mob Rules (and use Average Damage)!

I played my Shepard at an Epic this past weekend and the DM visibly shivered when I told him I was conjuring 8 wolves. Then I told him I'd be using the mob rules, asked what the combatants AC was, and within 90 seconds had placed the minis on the map and had resolved my turn. (And I didn't even add in advantage nor use the Knock Prone trait!)

He was very impressed.

Example:

11 AC - 4 Attack Bonus = 7. So using the Mob Tables: Every two wolves results in 1 attack that does 7 average damage. BOOM! Next Player...

Play Smarter, Not Harder...

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018For sake of those who (like me) where like "wait whaaaaaa I don't remember that?!?":

Dungeon Master's Guide. Page 250 if you've got it in physical form; or about halfway through chapter 8 if you're looking it up here on DnDBeyond.com.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018Two things I would like to add are...

One, the DM picking which creatures appear is great for a balance perspective (preventing the flying t-rex scenario), but the DM summoning random creatures makes it much harder for the player to prepare for how to their going to use them. Getting two Dire Wolves every time you use the spell is a lot different than getting two random CR1 beasts. If I, as a player, know what I'm getting in advance (be that what I ask for or something predetermined), I can prepare and be ready - DMs should keep that in mind as well when considering that the DM gets to pick what is summoned.

Two, just because you summon these creatures and they can attack doesn't mean you have to make your eight wolves always attack every round. You can have them use the help action to make the other party members stronger, you can use them to block a corridor to slow down reinforcements, you can have them all "engage" those seven ghouls and keep them busy so your player characters can focus fire more easily or pick off one at a time and so on or even have two attack at a time and the rest jump in as the first die.

Additionally, a lot of the things described as being a negative of these spells, like hogging the spotlight, have nothing to do with the spell itself and have everything to do with bad, self-centered, or simply new and unaware players. The idea of a DM saying this spell doesn't exist in your game because it can be problematic is essentially the same as the DM saying, "I don't trust you enough not to ruin the fun of the other players" or that they don't think you're competent enough to use the spell without being a problem. Imagine being a Wizard or Sorcerer and being told that one of their most powerful and most iconic spells (Fireball) doesn't exist because it's too powerful or that there is a possibility you might ruin the fun of the other players with it without even talking to you or giving you a chance. That's kind of a terrible starting point for a new campaign.

In conclusion, are the Conjure spells perfect? No. Can they more easily cause problems than most other spells? Yes. However, these spells can work just fine and they can be a lot of fun, but the key to their use is communication between the player and the DM. A responsible player will want to talk to their DM and work out the details of how the spells work before the game even starts so that they can reduce the chance of problems with these spells as well as reduce the work a DM has to do. A good DM should want to work with their players to try and make this basic and fundamental spell fun and useful for the players and not ban it outright because it could maybe possibly be bad.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018This is my understanding as well and based on the way Dispel Magic works with things like Bless, it should only dispel a single creature.

From the Sage Advice Compendium: "If dispel magic targets the magical effect from bless cast by a cleric, does it remove the effect on all the targets? Dispel magic ends a spell on one target. It doesn’t end the same spell on other targets."

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 25, 2018I like the idea of distributing control of the creatures among the entire party. Each player gets one or two creatures to control (depending on party size and summon count), and each creature takes its turn on its controlling player's initiative. Everyone gets a little extra out of their turns instead of just one person.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 26, 2018Why did they feel the need to change Summon Nature's Ally in the first place? Taking away consistency and player agency while simultaneously making more work for the DM and slowing down combat for everyone just seems like a lose-lose situation.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 26, 2018Looking at https://twitter.com/JeremyECrawford/status/798605326312292353 and then https://twitter.com/JeremyECrawford/status/950170649749696513 it seems that you would only be able to dispel one at a time, as casting it on the caster would not end the spell. (Casting damage on the caster might though!)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 26, 2018My house rules are if you are going to be summoning anything, then you have to have their stats pre-prepared before arriving at the session (this also means that they get to choose what they summon). Also, you all go on the same initiative, though reading the suggestion to allow the other players to control them sounds like a very good idea and I might try that if everyone is ok with it. Also you have to roll your hit and damage die at the same time.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Jun 26, 2018For as long as I've been a druid I've never thought of multiple low level beasts. I figured it'd be a waste of time due to their low HP. I usually did 2 beasts of 1 CR, numbers and strength mix. Giant Eagles to match my Aarakocra's flying style. But there are some good ideas here.