I love making maps. Making maps and sharing them with my players are probably my favorite parts of being a Dungeon Master. I chalk it up to reading The Hobbit and Redwall as a kid; both of those books began with detailed maps that laid out the story in a gorgeous, cryptic manner. They were like puzzles to be pieced together, like flowcharts made up of pretty boxes with all the connecting lines erased. I sat with these maps for hours before even opening the book, imagining what adventures could take place in the streets of Lake-Town or the forests of Mossflower as I plotted out my own adventures for Bilbo and the dwarves, and Matthias the mouse warrior would travel across the land on their quests. Then, when I actually read the books, I would constantly flip back to the first pages to trace the path the heroes truly followed.

I love making maps. Making maps and sharing them with my players are probably my favorite parts of being a Dungeon Master. I chalk it up to reading The Hobbit and Redwall as a kid; both of those books began with detailed maps that laid out the story in a gorgeous, cryptic manner. They were like puzzles to be pieced together, like flowcharts made up of pretty boxes with all the connecting lines erased. I sat with these maps for hours before even opening the book, imagining what adventures could take place in the streets of Lake-Town or the forests of Mossflower as I plotted out my own adventures for Bilbo and the dwarves, and Matthias the mouse warrior would travel across the land on their quests. Then, when I actually read the books, I would constantly flip back to the first pages to trace the path the heroes truly followed.

Maps in roleplaying games serve a similar purpose, with one major difference: the players of the game are both actor and audience. They have the ability to scour the map and imagine adventures that the heroes could embark upon, but they also have the privilege of actually being able to tell their DM, “I want to go there!” And there’s a good chance that they can! Depending on your style of game, there may be obstacles to overcome, a journey to complete, or an item that they must collect before they can reach that location, but there is an unspoken agreement between players and DM that if an area is marked on the map, the players can go there.

(There is another unspoken agreement in some games that if an area is not marked on the map or lies beyond its borders, the players cannot go there… but, well, sometimes DMs break the first agreement, and sometimes players break the second.)

So how do you create world maps that inspire the imagination just like Tolkien’s and Jacques’? The best world maps for RPGs possess three qualities: they are utilitarian, they are evocative, and they are aesthetically appealing. Let’s break these three things down into their building blocks, then I’ll show you how I make my maps. One thing to keep in mind while you’re reading this guide is that mapmaking is an art, not a science. Let this help you discover what about maps grabs your interest, and follow that passion.

Utilitarian Maps

In the real world, maps are made with a purpose: to help people navigate. (This isn’t technically true, there are plenty of historical maps designed for purely ideological or aesthetic reasons, but we’re not talking about those maps.) In RPGs, maps are made for many purposes, but the one that matters the most is this: to show players where they can go on adventures. If your map doesn’t show your players places where fun games of D&D can happen, it has failed as an RPG map.

In the real world, maps are made with a purpose: to help people navigate. (This isn’t technically true, there are plenty of historical maps designed for purely ideological or aesthetic reasons, but we’re not talking about those maps.) In RPGs, maps are made for many purposes, but the one that matters the most is this: to show players where they can go on adventures. If your map doesn’t show your players places where fun games of D&D can happen, it has failed as an RPG map.

The best maps highlight the best parts of your game. Don’t try to trick your players; burying your lede by making only the most mundane areas visible on your map will just make your players feel like your world is boring. It’s okay to have fantastic locations forgotten by time in your game world, of course, and it makes total sense to leave them off your map, but remember that your players will be looking at this map and trying to find places that excite them. Don’t hamstring your campaign by hiding all the cool stuff away.

A utilitarian map also has the basic need of being easy to read. Use clear fonts and understandable symbols so that your players can interpret your creation more or less correctly at first glance. Imaginative and artistic maps are nearly useless if you’re the only one who can decipher it. A utilitarian map could easily be a black-and-white flowchart, in which all of the major areas of your campaign are simple bubbles with words, and lines connecting them to show travel routes. This flowchart is an excellent way to create a rough draft of your campaign world, especially if the idea of making things look pretty intimidates you.

What About National Borders?

Games filled with war or political subplots, or that otherwise care about the geopolitics of their setting, may wish to note the borders of their nation-states… but note that Tolkien’s maps never spelled out the borders of Gondor or Rohan. Even the maps which appeared in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series—novels which lived and breathed war and politics—were generally coy about specific political borders. When designing a map for a game driven by war and intrigue, consider the following:

- Borders in pre-modern times were imprecise, and the regions in-between a nation-state’s well-defended heartland formed a vague marchland. Parts of these buffer zones often traded hands as the result of border skirmishes, making precise mapping of national borders a nigh-impossible task.

- National borders don’t physical exist, unless represented by a geographical feature like mountains or coastlines, or manmade features like the Great Wall of China. Borders are shorthand for many things in fantasy: a change in language, culture, climate, and many other factors. More important than borders are regions, broad geographical areas which are more concrete and less abstract than national borders. We’ll get into those later.

Evocative Maps

A map that succeeds at being usable is a good start, but a black-and-white flowchart does little to inspire the imagination. Evoking a mood with your maps is more than a matter of aesthetics (that part comes later). Rather, it is about creating landforms, names, and regions that get your players thinking at least one of three questions:

A map that succeeds at being usable is a good start, but a black-and-white flowchart does little to inspire the imagination. Evoking a mood with your maps is more than a matter of aesthetics (that part comes later). Rather, it is about creating landforms, names, and regions that get your players thinking at least one of three questions:

- “What’s happening there?”

- “What could happen there?” (or “What could I do here?”)

- “What happened there?”

All three of these questions are representative of your players engaging with your world on a deep level, be it the history of the world, the current crises (or status quo) of your world, or how they can make an impact of your world. Sometimes landscapes can have evocative effects purely through their aesthetic appearance. In one of my maps, the northern coast of the continent has been shredded into jagged and unnatural spikes. How did that happen? It’s just another question for the players to seek out as they explore the world.

Notably, regions with clear traits tend to immediately activate the imagination. A world map is made up of dozens of different regions, and you can easily divide a world in many different ways. My preferred way is to divide the world into geographical regions first—deserts, forests, marshes, etc.—as it gives my players something tangible to latch onto. (And perhaps it’s the Studio Ghibli geek in me, but there’s something almost explicitly fantastical about focusing on the diverse regions found in nature, rather than man-made boundaries.) You can also use cultural regions, too, or regions based on fauna. One can immediately understand the most important features of “The Plain of Endless Horses,” for instance, and see why a group of players might want to seek out such a place.

The clearer you make the divisions between these regions, the more immediately your players will understand the geography of your map. Clear divisions allow your map to be interpreted easily at a glance (see the point on Utility above), which makes it easier for your players to interact quickly and meaningfully with your world. If you want to make the divisions between regions less abrupt without losing clarity, consider creating border regions that combine traits of the two regions. A desert region and a steppe might be separated by a region of rocky badlands, slowly transitioning from the heat and lifelessness of the desert into the arid-but-vital steppe.

And finally, names of locations are vital to grabbing your players’ interest—but also make up one of the most subjective parts of mapmaking and worldbuilding. Names that excite you aren’t guaranteed to engage your players, but that’s just a matter of personal taste. If you don’t know your players very well, your best bet is to write things that excite you. Your players will sense your excitement, and—if all goes well—your own happiness will be contagious.

If you do know your players and their interests, you can leverage that knowledge to make a game world filled with names that remind them of their favorite fantasy media. If you have a player or two who love Lord of the Rings more than anything, go back to Tolkien’s texts and create some names that evoke the same archaic English feelings that the locations of Middle Earth do. Fans of the Legend of Zelda will be inspired by straightforward names that link geographical features to the cultures that reside there, like Lake Hylia, Gerudo Valley, and Kokiri Forest.

Aesthetically Pleasing Maps

This one may seem like a no-brainer, but it’s important for your maps to look good. And of all the art-not-science terms used in this article so far, “looks good” is by far the least scientific. As long as your map is easy to read and inspires your players to engage with your world, whether or not it “looks good” is irrelevant… but having a pretty map is always preferable.

These days, there are plenty of mapping tools that make creating beautiful maps simple. Inkarnate is a fan favorite, though one I have little experience using. Hexographer is another powerful tool which produces maps on a clear hex grid, creating a legible map at the cost of some aesthetic shine. But if you’re willing to spend a little extra time and effort, learning how to use Photoshop (or a free alternative like GIMP) to make your own maps is well worth it.

My Maps

To me, mapmaking is the primordial act of worldbuilding. It happens before a single line of text is written in my worldbuilding notebook. I will often revisit and revise throughout the worldbuilding process, but the creation of a landmass and its regions always kickstarts my creative process. I use pencil, paper, and a free image editing program called GIMP to create world maps for every campaign I’ve run in the past eight years.

Most recently, I made a map of the Republic of Auredane, the setting of Worlds Apart, an actual play D&D campaign I’ve been creating for the past year or so. Let’s look at that map as an example of my mapmaking process.

Freehanding

The first thing I do when starting a campaign is freehand a continent. I have a hard time dealing with blank pages, so it’s utterly transformative to put something, anything, down on paper. Once that’s done, then I can go back and add and revise to my heart’s content. I start by drawing an outline of the continent freehand on ¼-inch grid paper. Actually, I usually start with about a half dozen outlines, throwing drafts out and revising them until I have something I like the look of.

If there are any setting details I’ve decided on at this point, I draw them big and bold on the map. Everything else is pure aesthetic-driven discovery at this point. At this point, setting details will emerge as I find places for regions in the map I’ve created.

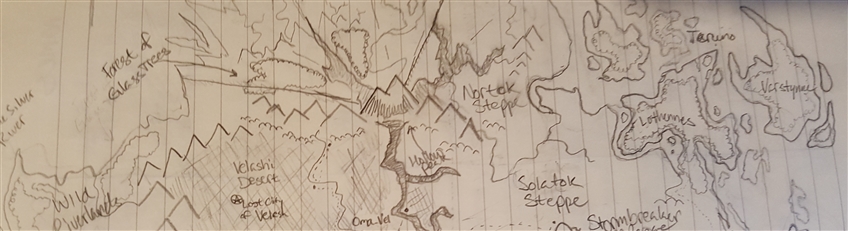

Once the outline is in place, I’ll start crafting regions and placing them in logical places in the map. This usually happens over the course of several days and usually involves doing more writing in my notebook than it does actually penciling things in on the map. Names will usually emerge at this point, too—though I have been known to just call regions “Swamp,” or “Desert” until an appropriate name comes to me. These names are usually just cool-sounding nonsense at this point. Actual meaning will arise as my brain marinates on these names for the next few days or weeks. Then, I’ll end up with something like this:

Inking

Once the map has been freelanded, I use a scanner or my cell phone camera to take a picture of what I’ve made so far. From here, I send the photo to my computer and import it into my image editor of choice. Using that image editor, I put a transparent layer over the scanned image of the map and use the paintbrush tool to trace the outline of the map onto the transparent layer. I also throw a hex grid into the mix so I can have some level of precision when placing terrain later. At this point, I have something resembling this:

Oceans

Remembering how to make oceans look good and pop is hard. I basically have to reteach myself how to do it every single time I make a map. Essentially, once I have my map outline, I duplicate the outline layer and fill in everything outside of the landmass with blue. Then I play with the opacity of the color until it looks nice and washed out (around 35% opacity usually does it for me) and delete the hard black outline from that layer. Then I draw in rivers (tracing over the original lineart again) using the same color blue as the ocean. The original outline layer then gets turned down to about 35% opacity too, so that the harsh black line around the edge of the landmass gets turned into a nice soft edge.

At this point, I grab a royalty-free parchment paper design from the internet and place it underneath my lineart.

Detail Work

Now that the basics of creating a map are taken care of, I can start adding details. I don’t have the patience to draw every single tree and mountain on my map, so I search online for brushes that me “stamp” trees, cities, and mountain icons on my map. There are lots available for free, but be careful if you plan on selling maps you make this way: not all brushes are available for commercial use. Anything goes if you’re only planning on using your maps privately, though!

My detail work is partially “tracing” over the features of my original lineart and part new creation. By this point, new ideas for regions and locations will have come to me and I feel compelled to act on them. Always accept those flashes of inspiration. Usually they’re great. And if they suck, well, you can always erase them later.

At this point, I’ll also use an airbrush tool to paint some light color over different regions to make them stand out. Light yellow for desert, with some green around oases and rivers, cool white for snow, deep green for forests, and so on. As locations are finalized, I use a fantasy font appropriate to the map (I prefer cursive fonts that appear handwritten) to write in any names and final legends. And voila! A map that excites my players, points out major regions and a few important adventure locations, and has a bit of aesthetic charm, too.

That’s it for world maps today. Next time, we’ll talk about regional maps and how they can help focus players’ exploration.

I’ve shown you one of my maps, now how about you show me some of yours? What do your world maps look like?

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist and the Critical Role Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting, the DM of Worlds Apart, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and Kobold Press. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his partner Hannah and his two feline cartographers, Mei and Marzipan. You can usually find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist and the Critical Role Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting, the DM of Worlds Apart, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and Kobold Press. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his partner Hannah and his two feline cartographers, Mei and Marzipan. You can usually find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018I made this map for my current homebrew campaign. Though it lacks plenty of details, it helps me and my players orient where to go and how to get there. I always add new details when the players discover them, such as this one where they discoverd a map portraying an ancient civilization that had cities in all the corners of the world. They quickly noticed that there was a nautiloid pattern (the golden section) hidden within, leading either to or from the one in the center of the ocean/world.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018I recommend Azgaar’s maps

https://azgaar.github.io/Fantasy-Map-Generator/

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018I am also a great lover of maps! While it isn't free, the program Campaign Cartographer is an excellent tool for those who absolutely love map-making. It's a little tough to learn, but it is a powerful program once you start getting used to it. This is the first map I made through it, which I've been using for an ongoing campaign for a little over a year.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018That right there. That's awesome! Thanks for this.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018that is awesome

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018This is the first map I've made for the campaign I'm about to begin. Surprisingly I've found that the world map was the easier part, I'm trying to find a method on actually populating it with areas my players can explore. Cities, forests, mountains, rivers, roads... it seems daunting.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018I always seem to end up with too much open space between things like mountains and forests and deserts. But this article has certainly motivated me to make another map :)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018This article couldn't have come at a better time! My wife and I are in the middle of creating a horrific plane of chaos and cosmic terror for our players (and hopefully, someday, all of you) and I've been trying to get inspiration and honestly a place to start on the maps for a few weeks! Thank you for enlightening us on your personal process, and for the helpful tools you provided. These will be well used in my home(:

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018Can't recommend this map making web app enough

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018I'm currently trying to create maps for my own campaign, as well as making some maps of a world another DM made for his campaign that I'm playing in, and this article is really helpful for figuring out an approach to doing it all. I've been using Inkarnate to create some more fancy maps before getting into anything mechanically detailed. Here's the first map I've made that I'd call mostly finished.

I personally really like to draw out my own landmasses without using generation tools or real-world references, but I've found both can be really useful for figuring out how landmasses work and what looks natural or not. Using generators for some inspiration is pretty great too, and being able to adjust parameters can make landscapes really unique and according to what you personally want.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018this was my first campaign DMing and the map looks like this.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018I really enjoyed this article! I bought a hand-drawn map of Mount Desert Island, where Acadia National Park is located in Maine, USA. This map alone inspired me to want to create an adventure set in this real world location. I then bought an art notebook and began drawing my own map with the tutorials I found online. I have been stumped on the actual how to. This article is exactly the new inspiration I needed. Thanks!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 15, 2018Here is a portion of my D&D map (the Northwest) that I made through Photoshop CS4: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Q-UbYBpj3JDCHoFo6QuO4aO-QcdXaJlX/view?ths=true

I used some tutorials and ideas from The Cartographer's Guild. My original map was hand drawn on hexpaper with colored pencils in 1986. I don't know how long this project took, but I am already laying groundwork for the other continents on the world.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018I use Azgaar's Maps to make my overall world maps (Gondolyn Map) , and Inkarnate to make individual cities and locations (Mont Map). Both are pretty great and easier than building from scratch. A little texturing and layering in Pixelmator is all they needed to be ready for players.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018thanks a lot will help

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018I love creating maps, from battlemaps to world maps it doesn't matter, I just love it! Here's a map I created for the current campaign, interactive. https://www.worldanvil.com/w/nordia-Zeay/map/40e78775-76ee-4fb5-8654-49e86a99995c

The party is currently in Lanteria, where they just defeated a corrupted Mayor who's ressurrected an old evil entity. They are now heading back to Kronia to take care of a Ancient Red Dragon.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018You should do a "Who is the most powerful Demon Lord"

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018This is really great and detailed practical advice.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018This has been very educational. I really do appreciate all the work that you do with every article you submit as well as the co-author work you did with the Tal'Dorei Campaign Setting. If you would not mind I was curious to know on the world which were the parts that you created? I have heard Matt say before that there were parts in the map that he gave you free range to do what you wanted for the world and left it to you.

p.s: I will post my map when I get a chance, since currently going to be running a Tal'Dorei campaing the map is kind of there already :)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Aug 16, 2018BEHOLD

The map I made for my game's region of Runewarren. Map making is my favorite, I saw the new article on the front page and got all giddy, haha. I've made a super quick tutorial on how I went about making the shoreline design: Link!