In the last article on this topic, I wrote about why we might want to run Dungeons & Dragons combat in the theater of the mind. Today I’m going to write about how. In my previous article I recommended watching two videos in which Mike Mearls and Chris Perkins run D&D games using the theater of the mind for combat. The first is Mike Mearls' Founders and Legends game. The second is the PAX West 2018 Acquisitions Incorporated game. If you want to see what running combat in the theater of the mind looks like, take a look at those two videos.

In the last article on this topic, I wrote about why we might want to run Dungeons & Dragons combat in the theater of the mind. Today I’m going to write about how. In my previous article I recommended watching two videos in which Mike Mearls and Chris Perkins run D&D games using the theater of the mind for combat. The first is Mike Mearls' Founders and Legends game. The second is the PAX West 2018 Acquisitions Incorporated game. If you want to see what running combat in the theater of the mind looks like, take a look at those two videos.

A Quick Summary for Theater of the Mind Combat

This is a long article so provided is a quick summary before getting into the details. You can use this summary to refresh yourself before you run combat in the theater of the mind.

- The DM isn't a competitor of the players but an adjudicator for the story.

- Running combat in the theater of the mind requires trust. Work with the players, not against them.

- Help players meet their intent. Ask what they want to do and help them do it.

- Start small. Run small battles in the theater of the mind to get used to the style.

- Each turn describe the situation from the point of view of the current character.

- Use quick diagrams if it helps clarify the situation.

- Assume enemies are within 25 feet of the characters and describe clearly when it is not.

- Adjudicate the number of targets in an area of attack based on its size and the current situation. Lean in favor of the character.

- Ask players to identify monsters by describing interesting physical characteristics of those monsters.

- Use evocative in-story descriptions to bring high fantasy to the battle.

- Unless it clearly makes sense otherwise, choose targets randomly to avoid perceptions of bias.

- Adjudicate edge cases as they come up based on the intent of the player and the intent of the spell or ability in question.

The Role of the Dungeon Master

It's important that we carefully understand the role the dungeon master plays when running combat in D&D and particularly in the theater of the mind. DMs are not competitors to the players. Our goal isn't to defeat the characters. When we run D&D using a gridded battle map and miniatures, it's easy for us to forget this role and start to think of it like we're the adversaries.

We are not our monsters. We are facilitators for storytelling and our job is to make the story as fun as possible and help the characters do awesome things.

It's important that we embrace this and that we also define it for our players so they understand that we are not the enemy; that we want to help them do awesome things as much as they do.

This requires trust.

Trust

In order for smooth and seamless combat in the theater of the mind to work, the DM must earn the players’ trust. This means talking to your players about how you're going to adjudicate combat in the theater of the mind and demonstrating that when a player tells you what they want to do, that you're helping them do it.

One great way to get players to embrace combat in the theater of the mind is when they realize they can do more than they could with a grid. Theater of the mind combat means combat can move faster than many players expect. It means they might have more options available beyond what’s listed on their character sheets. It means drawing them into the action.

Some players tend not to want to tell the DM exactly what they want to do. It feels like a competition to them and they want to hold some of their cards close. They might feel like the DM is about to spring a "gotcha" moment on them (and sometimes we do) so they want their own "gotcha" moments in return. This breaks the trust, however, and limits both the player and the DM in what they can do. To get past this, we have to describe what is going on each turn and ask continually for their intent.

Even when circumstances are dire, trust in your Dungeon Master means having faith that your DM isn't trying to trick you. Their villains may fight dirty with your character, but the human beings playing D&D around a table together are friends who want to see each other succeed.

Focus on Intent

"What do you want to do?"

This is the most important question in D&D overall and that doesn't stop when combat begins. The more details we have about what a player wants their character to do, the better we can help them achieve these goals. Instead of playing a guessing game, a back and forth between the DM and player to try to figure out what is going on, we can simply ask what the player wants their character to do.

This is a hard habit to get into. Often players will ask how far away an enemy is. We can easily tell them "about 25 feet" but we really want to turn the question around to "what do you want to do?" Unless the request clearly breaks the boundaries, they likely can do it. "I want to blast the boss sahuagin with a pair of eldritch blasts." "Done!"

This is a point we need to continually reinforce with the players. It’s important that we describe, each turn, what the situation is for their character. With that information in mind, we want the player to say what they want to do and then help them do it.

This intent can get quite detailed too. Characters with highly tactical options might have very particular things they want to do. We should continue to reinforce that stating their intent helps them achieve these particular things.

If player’s character is a glaive-wielding polearm master, the player likely wants to position the character so they can get the most options to hit incoming enemies. Okay! State the intent. "I want to position myself so I can hit any orcs that rush in." This not only helps us understand what drives the player but also how we can do it. We're more likely to throw orcs at this glaive wielding fighter because it's so cool to watch the character hack through enemies.

Ask for intent.

Start Small

If you or your players are used to running combat on a map with miniatures but want to try combat in the theater of the mind, start with small battles. Perhaps the characters run into a small patrol of bandits or goblins, fewer enemies than characters. Instead of putting out the gridded map and dropping miniatures on the table, roll for initiative and ask them what they want to do. This gets you and the group used to the style in a low-stakes situation.

Such battles might feel like a waste of time but, when we keep theater-of-the-mind combat as an option, the time spent on these small fights is significantly less than with a grid. Not every battle needs to be a significant challenge. Sometimes a small fight fits the story and theater-of-the-mind combat lets it flow right into and out of the rest of the game. These small fights might extend to battles that are a significant challenge where the characters face a single large monster, maybe even a legendary monster.

Simple fights like this usually have simple environmental areas (an open room, a hallway, a road, and the like), a single type of enemy (you can never go wrong with bandits), and a lower overall challenge (fewer monsters than characters with a challenge rating of less than a quarter of the characters’ level).

Starting simple with theater of the mind battles is a great way to get a feel for them and see how they work out for your players. As you get more comfortable with combat in the theater of the mind, you can try more complicated fights. You need not run all your fights this way, but having the experience lets you use it when the pacing of the game best supports it.

Describe the Situation Each Turn

When running theater of the mind combat, it is on us as DMs to describe the situation to each player on their turn. We focus on the details most important and most visible to their character. This may seem like a lot of work but it serves to reinforce what is happening to all of the players each turn, and gives the opportunity to reinforce story elements in addition to what would normally appears on a battle map.

When you get used to the capabilities of the characters and the desires of the players, you know to describe the things that matter to them.

A description might sound like this:

"Pommel, you are standing next to Tharmond and the mace-wielding gladiator. The mage who cast fireball is currently invisible, but you think you know roughly where he is. The assassin and spy have ganged up on Punchy who is about 20 feet away. The evil priest of Bane is still chasing butterflies from Tharmond's hypnotic pattern."

That is a pretty complicated situation so that's about as bad as it gets.

Fall Back to Quick Diagrams

I’m going to write about using abstract maps in a future article, but I’ll touch on it here. Just as there's no reason to always use a gridded poster map and miniatures for combat, there's also no reason to only use words and descriptions instead of jotting down some rough diagrams if it helps.

A piece of paper, erasable white board, or dry-erase poster map (I personally love using a single laminated piece of blank paper and a dry-erase marker) are extremely useful to jot down a rough map when it helps to clarify the situation in a battle using the theater of the mind. These need not be complicated. You can use dots or Xs or Os for monsters and characters. You can scratch them out or rewrite them if you want. Rough diagrams used as needed are much faster to use than arranging a full battle map and miniatures. Don't be shy to use whatever tools help the story move forward.

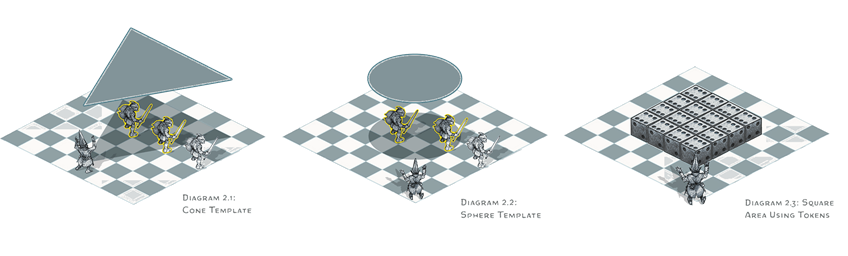

When playing on a grid, you can use templates and other game aids to quickly assess the area of a spell's effect. Learning to "eyeball it" instead is one of the greatest challenges of switching to theater of the mind play.

Adjudicating Movement and Distance

When running combat in the theater of the mind, we abstract some of the details of our characters and monsters in order to speed things up and put the focus on the bigger actions taking place during the game. The fact that a dragon is breathing out white-hot fire on our heroes or a wizard is tearing through the hordes of goblins with a roar of lighting is more important than the fact that an elf moves 5 feet further than a human.

D&D is a game of distances measured in 5-foot increments, however, so we can still use distances to describe what is going on. The cult leader can be 40 feet away behind an altar of obsidian and bone while his cultists, surrounded by impaled sacrifices, are roughly 20 feet away running in with daggers high. That's not hard to describe.

Mostly players want to know whether they can move up to someone with a move or not. Most of the time, we can just say "yes", and move things along. If it takes a Dash action to reach someone, we should mention that when we're describing it so it doesn't become a surprise that someone might lose their action to reach an enemy. Sometimes a move and a dash might not be enough if their enemies are really far away. Again, describe this ahead of time so it’s not a surprise.

To keep things simple, we can tell our players to assume enemies are roughly within 25 feet of the characters unless we state otherwise. This puts them in range of most ranged attacks and move actions. If things are further than that, we can describe those edge cases specifically. They too can assume that creatures are roughly 25 feet away unless we state otherwise.

When describing distances, we can use landmarks to identify important areas of the battle. The bone and obsidian altar can be one landmark. Nearby impaled corpses can be another. This helps players visualize the main features of an area in their minds.

Adjudicating Areas of Effect

Chapter 8 of the Dungeon Master's Guide includes guidelines for determining how many creatures fall within an area of attack. These are good guidelines but doing a bunch of math to figure out the number of monsters isn't always the fastest approach. Instead, we can abstract areas of effect into tiny, small, large, and huge areas.

Tiny areas, like the 5-foot range of the spell green-flame blade, can likely and hit one or two creatures. Small areas, like a burning hands spell, can usually hits two or three creatures. Large areas, like the blast of a fireball, cone of cold, or lightning bolt can likely hit four to eight creatures. Huge areas, like the blast of a circle of death, can likely hit eight to sixteen creatures.

Many times, as a dungeon master, you'll let the players know how many enemies they can hit with an area based on the circumstances. If a bunch of goblins are in a small tunnel, a cone of cold will likely hit them all. If four evil mercenaries are all spread out, a fireball might only hit two. Because we want our players to embrace this style of play, we should err on the side of being generous. People are a lot more amenable to combat in the theater of the mind if they're getting things out of it they know they wouldn't get on a gridded battle map.

Identifying Monsters

When we're running a battle completely in the theater of the mind, it can be easy to lose track of each individual enemy. One way to help players identify enemy combatants and draw them into the story is to ask them a very simple question:

"What is an interesting physical characteristic of this enemy you face?"

This lets the player come up with interesting notable characteristics of the enemy and also helps everyone else at the table know which enemy they're facing. We can write these characteristics down as the identifier for the monster when tracking damage and the like.

"This goblin is wearing a bright blue beret" now becomes "blue beret goblin" and everyone knows which goblin we're talking about.

It's a simple trick that gets the players into a more creative mood and solves the problem of monster identification within the story so it doesn't devolve into "goblin 3."

Ask your players to identify interesting physical characteristics of monsters and you have a unique way to identify that monster in your narrative combat encounter.

Use Evocative In-Story Descriptions

Our descriptions need not end with monster characteristics either. Since we have no visual representation of the location or monsters, it’s up to us to describe what is going on. Using only game mechanics to describe the action removes the fantastic action taking place in the world.

Use evocative in-game descriptions. Don’t worry about sounding silly or overly flowery. Describe what the characters are seeing and avoid purely mechanical or numeric descriptions.

This is a game of high fantasy and our words can be as powerful, even more so, than the best fantasy movies we’ve seen if we give ourselves permission to let go.

Using only your voice and body language, how would you describe this spell?

Choose Targets Randomly

Sometimes it's clear which character a monster attacks given the circumstances of a fight but many times it isn't so clear. In these cases, rather than choosing ourselves, we can let the dice choose for us. Rolling randomly to determine the targets of monsters helps us avoid any unconscious bias we might have for or against any of the characters and it also helps to project that lack of bias to our players. If it isn't clear who a monster attacks, let the dice decide for you.

Adjudicating Edge Cases

Though the fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons isn't the most complicated version of the game, there are a lot of mechanics available to characters during combat. Class abilities, spells, and feats all have lots of details about how they work including specific distances, ranges, and areas of effect.

No single method of running combat can account for all of the particulars of these mechanics. There is no simple theater of the mind ruleset that can handle all of these details at once.

Instead, dungeon masters who run combat in the theater of the mind have to individually adjudicate how these mechanics work. We can once again return to the intent; both the intent of the design of the mechanic and the intent of the player when their character uses it. What was the power intended to do? What does the player intend to do with it?

I’ll dig deep into handling edge cases in a future article. For now, consider what makes sense for the specific situation given the intent of the ability or spell and the intent of the character.

A Focus on High Adventure

Previously we talked about why we would want to run combat in the theater of the mind in the first place. How we run combat should depend on why we want to run it. Our intent with combat in the theater of the mind is to stay true to the story and pacing. We want to focus our lens on high fantasy and fast action. When we run theater of the mind combat, we're willing to shave off some of the tactical details of combat in order to keep things moving quickly from scene to scene while capturing the high fantasy and adventure that Dungeons & Dragons brings to our table.

Hopefully this short guide gave you good ideas how to incorporate theater of the mind combat into your toolbox to keep your game running fast, smooth, and fun.

Mike Shea is a writer, Dungeon Master, and author for the website Sly Flourish. Mike has freelanced for Wizards of the Coast, Kobold Press, Pelgrane Press, and Sasquach Games and is the author of Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master, Sly Flourish’s Fantastic Locations, and Sly Flourish’s Fantastic Adventures. Mike lives in Northern Virginia with his wife Michelle.

Mike Shea is a writer, Dungeon Master, and author for the website Sly Flourish. Mike has freelanced for Wizards of the Coast, Kobold Press, Pelgrane Press, and Sasquach Games and is the author of Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master, Sly Flourish’s Fantastic Locations, and Sly Flourish’s Fantastic Adventures. Mike lives in Northern Virginia with his wife Michelle.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018This is great; thanks.

Having a few strong core principles (that the DM is an adjudicator of combat, not competing against the player characters, and should generally resolve ambiguities in the players' favour) really helps to resolve those completely unpredictable cases that may crop up from time to time.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018In theater of the mind, how do you deal with characters that have chosen a race with a movement penalty or bonus? I find that in most theater of the mind combats, the DMs go with the proverbial "sure you can get there" and "sure you can reach it". So the Dwarf that is getting all the benefits of that race suddenly gets to ignore their main disadvange of only 25ft movement and the player that purposely picked a race with 35ftmovement suddenly gets nothing out of it.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018This very point will be addressed in a future article. Stay tuned!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018Could just be my imagination, but some of these points seem to be referencing comments on the previous article. In any case, it's still nice to see those things addressed (in some form).

As a DM myself, I would also like to stress that we are human like everyone else, and players can help greatly by reminding when we miss or forget something.

Sometimes, it might seem like the DM is trying to cheat when (to take an example from the previous article) some of the hobgoblins you are fighting suddenly appear behind your line of fighters, and start hitting your casters. But, I can assure you that (most of the time), it's just that he's made a mistake, and simply asking "how did they get past out battle line?" will sort things out.

Arguing with your DM may be problematic and disruptive, but a simple comment to ask questions or point out mistakes can be a much appreciated help.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018Great article, as usual. Although I do love me some tactical combat on the grid, I'm going to try this (tonight!) with a low-level one-shot adventure. The adventure is almost entirely outdoors, so there really isn't the need for a map or grid anyway.

Also, as I read the article, I can't help but be reminded that "theatre of the mind" is exactly what we use when we read novels. It is rare to have any kind of drawing, let alone a tactical map, to help us imagine the scene playing out. And it works just fine - we don't obsess over the details, and we can imagine the scene using our own imaginations.

I doubt I'll ever give up tactical combat entirely for TotM, but I'd like to start using it for quicker, less complex fights.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018As James mentions, I do get into this in a future article. In short, though, how much does an extra 10 feet of movement between a dwarf and a wood elf matter? Of all of the main mechanics in D&D that turn into actions within the story, moving 10 feet isn't as big a deal as hurling a fireball or cutting down an ogre with a pair of blades.

A DM can account for this extra movement by, sometimes, making it clear that the elf got somewhere the dwarf cannot. Distance doesn't have to be totally abstracted. Instead, the DM can mention that the wizard is 30 feet away and the player of the dwarf knows they'll either have to dash or use a ranged attack.

Most of the time, though, I'd say the extra ten feet isn't that important but it might be important to you or your player (or DM). A conversation is worth the time ahead of time.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018Great article, thank you! I particularly love the idea of asking your players to name specific characteristics of the baddies they're fighting. Definitely more interesting than "Bandit #3"!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 12, 2018THe DM needs to be aware of these cases, and bring them up from time to time. IE, "dwarfy, you can't quite each him this turn without dashing" or "only mr monk can get to him with their movement alone"

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018Thanks for the great article!

Another great benefit I've found for TotM as a DM is it saves me a lot of time on prep (and major cash on minis) and allows for a lot easier improvisation. Now when my group decides to not go into that cave that I drew a map of and prepared all the minis for and instead goes into the haunted forest, I can easily set up another encounter on the fly.

I find for my players TotM gets them out of tactical min/maxing world and more into their own imaginations and they end up having a lot of fun improvising the fight. It feels more like reading a really immersive book instead of playing a video game/board game.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018I've recently started a campaign with friends, but we are all in different cities now. Before we started, I really was struggling on how to run combat, and was leaning towards Theater of Mind for convenience, but did not want to at first as to not detract away from combat. Your articles have really helped reassure myself in knowing that Theater of Mind can still be a lot of fun, and in many cases, even more fun. Thank you for working on and publishing these articles at such an opportune time. I really couldn't be more thankful for this strong and helpful advice!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018What a wonderful read I've had! Thanks for this Mike!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018Thank you this article is really useful, I just used the tips you gave.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018Great article Mike. I'm a grid and minis man myself, but I always enjoy reading your stuff.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018Great article, thank you! Ive always ran my games with a blend of both totm and tactical/miniatures; I happen to love mini's, but some scenes actually work better when the player's actively use their imagination.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018I like TOTM. For me, it's the best. It makes dnd more social, fun, and imaginative. Always glad for more articles on the subject because I don't do it very well! :)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018What you have to remember is that those things come into play when they matter and otherwise don't affect the story, so it's really a deliberate choice on the DM's part as to what matters in any particular scene or conflict. I usually run games in TotM and I use things like Speed stats only when it becomes relevant.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018I've been playing D&D since the fifth grade, when one of my friends got the BECMI red box basic set for her birthday. Most of the groups I've been involved with have used a combination of tactical grid and Theater of the Mind and enjoyed doing so, but the current group that I am DMing for is extremely resistant to trying Theater of the Mind.

I think it might have to do with the fact that three of the four players are fans of Critical Role, and even though my VTT maps are a far cry from Matt's Dwarven Forge dioramas the players really seem to enjoy engaging with them. I've attempted to try TotM for smaller encounters, but the players want tokens on the screen.

Does anyone have any ideas on convincing reluctant players to try Theater of the Mind?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 13, 2018Maybe you should try to show them some combat when what is like when you use theater of the mind, I've always used theater of the mind, but it seems like they have not. If you show them, maybe what it is like for another group, maybe they'll try it. Good luck!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 14, 2018Thanks so much for a great overview of this subject Mike. I must admit that I often run over-complicated combat with too much map making and mechanics and I really want to let loose and go with TotM.

On the plus side, I have seen you in action and hope to learn more as the sessions stack up.

Again, awesome artcile!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Dec 14, 2018Hi Jerry!!