Here’s how you can build a believable campaign setting where legendary monsters shape the landscape itself, and leaders react to their power. This is a setting where gameplay comes first, and your players can make a difference, rather than groveling before king so-and-so and collecting the next quest to kill a generic group of monsters. All you need to start are the free D&D Basic Rules—but having a copy of the Player’s Handbook, a Monster Manual, and a Dungeon Master’s Guide will make your worldbuilding much easier and much richer.

Building Legendary Worlds

So far in this worldbuilding mini-series, we’ve talked about how to subtly portray your world to your players through both equipment and through encounters—random or otherwise. We also delved into how to start building your first-ever D&D world in New Player’s Guide: Building Your Own Campaign Setting. That article encouraged new DMs to start small, focusing on an area of only 100 square miles—that is, a 10-by-10 mile square—centered on a settlement that characters can use as a home base.

This article is one lens through which you can start building believable worlds bigger than the 100 square mile area we created last time. Let’s set our sights higher, creating a 10,000 square mile area—that is, a 100-by-100 mile area—and populate it with monsters that are far too powerful for your party to defeat. In fact, populate this location with monsters that are so powerful, your players shouldn’t even get close enough for them to shout ill-advised insults at it for at least 10 levels.

That might seem like a strange thing to say; if you’re building a game world, why would you fill it with monsters that the players aren’t capable of fighting for months, maybe even years of real-world time? Why would you create a map, and drop a kraken, an ancient red dragon, and a beholder onto the map, knowing full well that their lairs are essentially no-go zones for the next ten levels? The answer is simple: because despite all appearances, the monsters in the Monster Manual aren’t just there to be fought, killed, and looted.

These monsters aren’t combat challenges—not for a while, anyway. By placing the lairs of incredibly powerful creatures around the map, you create social interaction and exploration challenges for the players to contend with. Remember the three pillars of D&D play described in the Basic Rules? Dropping a number of mighty, legendary monsters into the setting will give you the tools you need to help your players engage with the game on all three pillars—exploration, social interaction, and combat.

Choose Some Legendary Monsters

Some monsters in D&D are so powerful that their lairs warp the landscape around them. These changes range from altering the weather to warping the land itself with magic—and some even affect the minds of the nearby wildlife. Not all legendary monsters possess this power, not even all monsters with lairs, so the creatures who possess these Regional Effects are listed below. They range from the mid-level boss monster known as the aboleth to the final boss-level ancient red dragon. Start by choosing three monsters from the list below. These will be your legendary monsters, whose presence affects the land and the politics of the region around them.

Monsters with Regional Effects (Sorted by CR)

This list only includes monsters found in the Monster Manual. Legendary creatures with Regional Effects from other sources, such as Volo’s Guide to Monsters, Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes, and the many D&D adventures, aren’t included here.

Now that you’ve selected your monsters, take a look at their Regional Effects. You can find that information in their description, just beneath their Lair Actions. If you like the effects presented, great! That’s basically proof that you made a good decision. If you aren’t a fan, feel free to throw that monster back into the pool of options and pick out another. Once your list is solid, it’s time to map a map.

Mapmaking

If you made a province-size map in New Player’s Guide: Building Your Own Campaign Setting, you know what’s happening here. Now it’s time to expand your local map into a kingdom-scale map. This doesn’t have to literally contain a kingdom; it might be largely wilderness with a few city-states and towns as “points of light” in a mysterious and monster-infested land. That style of play is extremely conducive to fun D&D campaigns filled with exploration and monster-slaying. Try making a points of light-style map here!

Mapmaking Basics

Start by choosing a scale. Last time, we made province-scale map was a 10-by-10 grid of squares, in which each square was 1 mile wide. This time, we’ve zoomed out, but the physical size of the map is still the same. We still have a 10-by-10 grid of squares, but this time each square is 10 miles wide. Put another way, that means each square on this kingdom-scale map is the size of the entire 10-by-10 grid of your province-scale one! Start by placing your original province in the center of the map, just for ease of use.

The Dungeon Master’s Guide recommends 6-mile hexes as the unit of measurement for kingdom-scale maps, rather than 10-mile squares. Both options are equally valid! 10-mile squares were chosen for this guide because it allows the entire province-scale map to fit into a single square at this scale.

The next step is creating a landmass. An easy way to do this is to create a coastline and an ocean on one side of your map, and have the other three sides trail off into more land. A few rough squiggles on your map are totally sufficient for a coastline at this scale. If you want more tips on how to make a believable map for your campaign, such as including features like forests, rivers, and mountains, check out Mapping Your Campaign in chapter 1 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Step three is placing cities and towns. In an area where civilization is strong, an area of this size will likely have 3 or 4 major cities and 5 to 8 towns. If this area is mostly wilderness, such as in a points of light setting, there will likely only be 1 or 2 cities and only 3 or 4 towns. Just like the Dungeon Master’s Guide recommends, don’t worry about little villages at this scale. Simply choose a square on your map for this city to exist in. Where exactly that city or town is within the square isn’t important at this scale; you may never have to pin down the city’s exact location within the square.

All of the details of these cities—who’s in charge, what their economies are based on, what problems they have, and so forth—are left to you to determine as the Dungeon Master. The Settlements section in chapter 1 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide has your back if you want a little help getting started. Now that you have these basics down, it’s time to insert your monsters and have them shake up the world.

Insert World-Changing Monsters

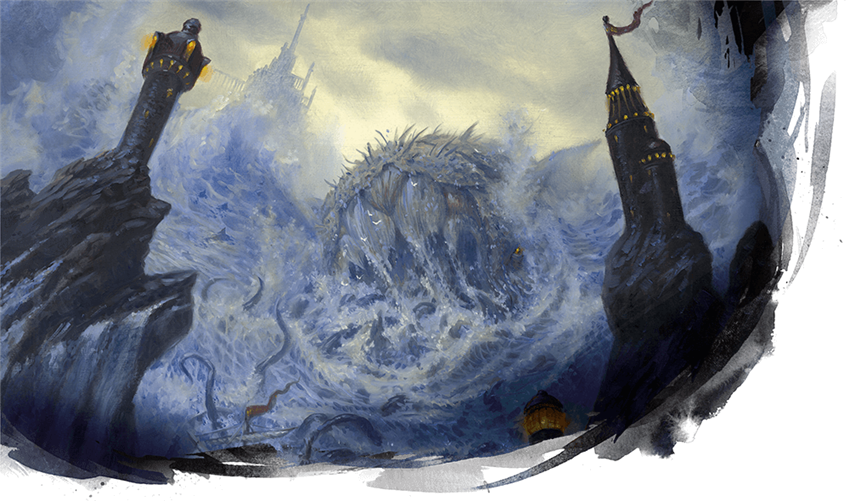

Imagine living in New York in the ‘30s and King Kong survived his clash at the Empire State Building. He’s made his own lair about 40 miles north of Manhattan. Or you’re living in Tokyo and Godzilla decided to make a lair in mountains of Saitama, about 40 miles away. The landscape slowly changes because of their presence, not just because King Kong and Godzilla are enormous beasts that eat an unimaginable amount of vegetation and wildlife each day, but because they’re magical beings. When they settle in one place, that magic settles too, making the landscape more suitable for them.

Jungles begin to grow from the upstate New York soil, and common lizards begin to grow larger and larger until they’re dinosaurs.

Take the three monsters you’ve chosen and select a square on your map for each of them. Most monster lairs are at least 30 miles away from a major population center. These legendary monsters tend to be practical beasts, choosing not to tangle with their powerful neighbors unless they can help it. A dragon known throughout the region might make its lair as far away from cities as possible, and in dangerous terrain. The dragon can fly, after all, so it doesn’t mind making a 75-mile trip to ransack a city that fails to pay tribute.

If the square you chose is right next a city, think of a good reason why the city hasn’t retaliated with its army and driven the monster out. Maybe the monster rarely bothers the people of the city, so they leave it alone to avoid provoking its wrath, like the relationship between Smaug and Lake-Town in The Hobbit. Or perhaps the monster recently attacked the city, annihilating its defenses, and the city is being plundered by the monster’s minions while the city’s populace is forming an underground resistance movement.

Warp the Landscape

Like we mentioned before, these monsters have Regional Effects that warp the land around their lair. Let’s settle an adult blue dragon in a ruined pyramid about 50 miles away from a large city. The Basic Rules (or Monster Manual) gives us three Regional Effects to choose from, and we can select one, two, or even all three. Choosing more effects will almost always guarantee that you create a more memorable location and monster. That’s almost always the correct option, unless there’s an effect that you just dislike.

The adult blue dragon’s effects are:

- Thunderstorms rage within 6 miles of the lair.

- Dust devils scour the land within 6 miles of the lair. A dust devilhas the statistics of an air elemental, but it can’t fly, has a speed of 50 feet, and has an Intelligence and Charisma of 1 (−5).

- Hidden sinkholes form in and around the dragon’s lair. A sinkhole can be spotted from a safe distance with a successful DC 20 Wisdom (Perception) check. Otherwise, the first creature to step on the thin crust covering the sinkhole must succeed on a DC 15 Dexterity saving throw or fall 1d6 × 10 feet into the sinkhole.

The 6-mile radius of these effects fills the entire square this dragon’s lair inside and then spills over just a little bit into all of the surrounding squares—assuming the dragon’s lair is in the dead center of the square. If you’re using 6-mile hexes, try situating the dragon’s lair on the point where three hexes meet, thus filling three hexes with these Regional Effects.

Now when the characters enter squares or hexes affected by the blue dragon’s magic, you can show off its awesome power without forcing low-level characters into a doomed battle with a CR 16 monster. The raging thunderstorms and hidden sinkholes give you an opportunity to create tense exploration encounters. For example, your party of 5th-level characters are exploring the desert around the pyramid, and encounter a hostile dust devil or two. These monsters are strong, but not overwhelming, so they continue closer.

When the pyramid comes into view on the horizon, they see a massive thunderstorm coiling around it, and they see a huge blue dragon swooping through the storm, battling a trio of fire giants foolish enough to try and claim its lair for themselves. From this distance, perhaps of about 5,000 feet away, they watch one fire giant die horribly from the blue dragon’s lightning breath, and then the other two start to flee—straight towards the characters! One of the giants falls into a sinkhole and gets stuck, making him an easy target for the dragon, who swoops down and bites his head clean from his shoulders. The dragon stops for 1d6 rounds to messily devour its prey.

The other giant continues to flee, and that’s a good sign that the characters should, too. Now, they have to outpace the last fire giant in a mad dash away from the dragon’s lair. If they fail to do so, they might have to bargain for their lives with the (now rather full and easily amused) blue dragon. Maybe a rare magic item will buy their freedom. Or perhaps the dragon wants the characters to undergo a quest in the nearby city in order to expand its dragon cult and expand its influence in the region. As the DM, the choice is yours. You can use the Villains section in chapter 4: Creating Nonplayer Characters of the Dungeon Master’s Guide determine this dragon’s personality and its desires.

Twist the Political Landscape, Too!

As you can see from the encounter above, intelligent monsters aren’t content to just wait around for adventurers to come kill them. They have goals and motivations, and they’re interested in making alliances (or making others their servants or mind-dominated thralls) and growing more powerful. Using your own imagination or the tables in the Villains section in chapter 4: Creating Nonplayer Characters of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, think about what your legendary monsters’ motivations and personalities are. Take notes on how such a monster would interact with the governments of the nearby cities and towns—and even the nation that they reside in, if your region has a national government.

If your campaign doesn’t have a strong national government—and it doesn’t have to—consider including factions in your campaign. These factions are loose organizations of like-minded individuals who want their group to gain greater power in the region. Some factions are good, like the Harpers in the Forgotten Realms. Others are evil, like the Emerald Claw in Eberron. And many more have no strong moral philosophy, only an ethos of self-interest, like the Lords’ Alliance in the Forgotten Realms. These factions tend to want to manipulate powerful monsters to further their interests, and they may want the characters as their allies, too.

If your characters aren’t terribly self-motivated, having two or three competing factions vie for their support could be a way to goad them into action. For more information on factions, check out the Factions and Organizations section in chapter 1 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Zoom Out

You’ve just done a lot of work, creating a landscape, placing cities, monsters, and even thinking about factions and politics in your world. Take a break from this worldbuilding and think of something else for a moment. Watch a video, listen to some music, play a game, take a shower. Once you’ve given your mind a moment to rest, come back to your notes. Look it over—does this stuff make sense? Even more vitally, does it seem fun to you? When you look at your map, does it inspire interesting stories? Do you want to add more monsters or cities, or would you prefer to make things a bit sparser?

Sometimes, the only way to learn the answers to these questions is to play D&D! If you don’t know either way, take your setting to your friends and start playing! This setting you’ve created is a living document—the only person who knows all the intricacies of it is you. The only cardinal rule of modifying a setting on the fly is don’t break your players’ immersion. Your players won’t know that you moved the distant dragon’s lair to two squares west of their current position unless they’ve already met that dragon or heard stories of its far-off roost, so don’t worry about playing fast and loose. Everything you do is in the service of making your game more fun.

That’s it for the Worldbuilding mini-series! Are there other worldbuilding topics you’d like to see covered in the future? Let us know in the comments!

Create A Brand-New Adventurer Acquire New Powers and Adventures Browse All Your D&D Content

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus, and the Critical Role Explorer's Guide to Wildemount, a member of the Guild Adepts, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and other RPG companies. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his fiancée Hannah and their animal companions Mei and Marzipan. You can find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus, and the Critical Role Explorer's Guide to Wildemount, a member of the Guild Adepts, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and other RPG companies. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his fiancée Hannah and their animal companions Mei and Marzipan. You can find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020This is a great article! My friends and I have been using these to build a world together and they've really helped. I think it would be cool to see how spells effect a world and influence the cultural landscape of a region. Overall though, an amazing article and mini series! Keep up the good work!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020This is genius! Start with a legendary monster, and work out how their presence affects the land and politics around them!!

"By placing the lairs of incredibly powerful creatures around the map, you create social interaction and exploration challenges for the players to contend with."

That sounds so obvious when you mention it, but it never occurred to me before reading your article. Thanks, James!

PS: I especially enjoyed the worked examples in the article - like King Kong jungles around NYC and the blue dragon vs giants battle leading to an escape encounter.

EDIT: Now that I've read the article a second time, I think I'd like to see a worked example for the political section too. For example, how would the presence of that blue dragon affected the surrounding cities and alliances?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Love the escapable encounter w/ blue dragons and fire giants. Really cool idea! Any ideas on a campaign set in the giants/dragons war anyone???

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Seconded! I'd love to see a "Worldbuilding through spells" article too!

I also like the idea of "living spells" - like detect magic and dispel magic goes awry, merges, and becomes a living entity: a magic-eating mist on a quest to find and snuff out the existence of magic in a region.

(Inspiration: https://dmdave.com/5-living-spells-for-dungeons-dragons-5th-edition-living-magic-missile-mage-armor-sunburst-dispel-magic-and-mage-hand/)

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020If you mash Tyranny of Dragons and Storm King's Thunder together, you've basically got it all set! Throw in the Ring of Winter plotline from Tomb of Annihilation, the frost giant chapter that was cut from Tyranny of Dragons, the classic Against the Giants adventures in Tales from the Yawning Portal, and maybe even Maddgoth's Castle from Dungeon of the Mad Mage for good measure, and you've got lots of material for a great gianty, dragony story!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Great article! I never thought of how much of the world is affected by monsters, even when they aren't directly threatening the PCs. I love the dragon and giant encounter. Great work!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Super cool, and I have accidentally already used this in my campaign! The first is that a Kraken lives beneath all the islands. The second is a Dragon turtle that has a coral reef on its back. Way too powerful for 2nd level, but they loved the turtle reef.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020First step is how it affects war and medicine. Then you can fill in gaps from there based on rarity.

Example: Healing magic is very common and cheap, so no one bothers to advance medicine. This means in areas where healing magic isn't found there is lots of death and disease.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020That's awesome, mind if I steal it?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Cool article. My group of 4/5 first time dnd'ers are getting to the point where they can start fighting some of these tougher monster. Looking forward to using the advice. Small connection in the beginning - 100 x 100 miles is 10,000 square miles, not 1000

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Excellent series! Thanks!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Not at all. Running the game in Bilgewater, Runeterra. The world of League of Legends.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Thank you for this article. I am currently preparing a new campaign for my players, and as a new DM in training (with the help of my DM on another RPG), this series of Worldbuilding articles helps a lot.

And thanks to this article precisely I added a few monsters with Lairs effects and it seems... More DnD to me now. More fun to play, more fun to tell.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Good catch, thank you!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 24, 2020Fantastic article and one I will be using to great effect in my campaign! I would like to ask you about scale for a world. I have just designed my own world and mapped it but I am unsure how big to make it in terms of the km size of land masses and such. What would you recommend James?

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 25, 2020Using the monsters region effects is neat idea in establishing what is in the world

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 25, 2020It's always easier to start small. You're much better off expanding a small area (or adding a neighboring island, etc.) than trying to stretch your precious, limited prep time over a too-big area.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 25, 2020Very helpful post. My party just vanquished Irymrith the ancient blue dragon (can never spell that right) from STK, and her regional effects really helped my players feel the gravity of her presence.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 25, 2020The Zhentarim might be a better example of an evil faction. The Blood of Vol is more of a philosophy than a political faction. The Emerald Claw is decidedly evil, though.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted Apr 25, 2020Sounds familiar... :P

I spotted a missing space here:

Also, is this an unofficial monster statblock, created for this article? Seems like the first time you guys have used the non-homebrew system for that.

Anyway, great article and series!

EDIT: Also, thanks for that Frozen Castle DMsGuild link. I had no idea it existed! Was it actually cut from Tyranny of Dragons, or was it just later created as supplementary content?