Welcome to New Player’s Guide, the first stop on your journey to playing D&D. This series has advice for players who’ve just joined their first D&D campaign, as well as Dungeon Masters who want help taking their new campaign to the next level. To see the other articles in this series, check out the New Player’s Guide tag—and for the brass-tacks information on how to start playing D&D, click on the New Player Guide link at the top of this page!

Hold up, Dungeon Master! This article follows up on last week's installment of New Player's Guide: How to Try Tactical Combat. If you haven't read that article yet, start there.

You can bust out a map and miniatures for as many encounters as you want, but those alone don’t make an encounter tactical. They’re vital components, but they’re not the only part. Tactical combat encounters tend to be more complex than other combat encounters because tactics involves decisions. If your encounter takes place in a featureless 40-foot-by-40-foot square room with three hobgoblin warriors, neither you nor your players are going to feel mentally engaged.

Let’s talk briefly about the first thing most D&D players think of when the word “tactics” is mentioned: maps and miniatures.

Are Maps and Miniatures Tactics?

With the sole exception of funny-shaped dice, what could be more iconic to D&D than a map split into 5-foot squares and little plastic or pewter miniatures that represent the heroes and monsters? These game aids aren’t necessary for tactical play, but they do help answer the questions “Where are we? What does the area look like? And what might be dangerous to us?” quickly and visually. Those are the sort of primeval, monkey-brain question that anyone might ask in a potentially dangerous area like a monster-filled dungeon.

You don’t necessarily need to include maps and miniatures in every encounter. It’s totally reasonable for a DM to run simple encounters with only one or two monster types and simple terrain solely in the Theater of the Mind—that is, simply describing the encounter and having every player imagine the battle solely in their minds’ eyes. And then you bust out the maps and minis when the characters start an encounter with lots of tactical depth.

Having a persistent representation of the game world is vital when you start layering complex tactical information on top of a combat or exploration scenario. If you’re worrying about five different types of enemies and three different types of traps, and your players have cast grease on a specific part of the map and spirit guardians on another part—well, there’s no way every single player can keep all that information straight in their heads. When encounters get complex, the Theater of the Mind breaks down and arguments start happening.

“I was more than 60 feet away from the beholder, it couldn’t have hit me with its disintegration ray!” one of your players might say, understandably upset when their beloved warlock is turned to dust by a beholder they thought they were safely distant from. When you have a map divided into 5-foot squares and use miniatures to mark every creature’s position, it’s easy to resolve arguments like this. Just count the squares.

And if you aren’t worried about mishaps like this, you don’t need to include a grid. Just draw or upload an ungridded image and place miniatures or digital tokens on it. This way, you can have a map with relatively abstract distances for fast-and-loose play while still benefiting from seeing everyone’s relative positioning on the map.

However. Even though maps and miniatures are an iconic part of tactical D&D play, focusing solely on the physical representation of the game misses the forest for the trees. There are three core components of tactical play that go far deeper than just rolling out a map and placing figurines or tokens on it. If you want to build encounters that can only be played in a tactical style, then you need to go beyond simple maps and minis.

The Building Blocks of Tactical Gameplay

Whenever you sit down to create a tactical encounter—or when you start thinking about how to spruce up an encounter you found in a published adventure—start by thinking about the three fundamental components of encounter design.

- Terrain

- Monsters

- Win conditions

Let’s break these down. You don’t have to figure out all three for every encounter you create, but try to consciously include at least two elements, and think deeply about at least one of them. Doing this will instantly make your encounters more engaging.

Terrain and Positioning

Just like every part of tactical design, a great encounter has terrain that does double duty: it makes the tactics more interesting, and it tells a compelling story. Consider how we could improve this encounter area, an ancient temple’s treasure vault:

This vault is 40 feet wide and 80 feet long, and its floor is covered with coins and jewels. At the far end of the hall is a statue of a woman in sacred regalia. Hidden beneath piles of gold are concealed pit traps with deadly spikes at the bottom. Eight skeletons with longbows and ceremonial longswords, all of whom attack the characters as they enter. At the back of the room is their master, a lamia who wishes to annihilate the interlopers, though she tries to force the characters to surrender so she can trick the characters into accepting a geas that will compel one of them to kill the others for her amusement.

This is a great encounter, but it could be made better and even more tactical through the use of compelling terrain. Here are three ways you can do this through terrain alone.

- Create elevated terrain; perhaps four pairs of 10-foot-square areas that are elevated 20 feet above the ground, spaced every 15 feet down the hall. Position the skeletons atop these pillars, allowing them to safely shoot at the characters from afar as they try to run down this hall. Also, make the statue a gigantic piece of terrain that fills the entirety of the back wall. Her cupped hands can be a 5-foot-by-10-foot platform that the lamia rests on, about 30 feet above the ground. This gives her an unimpeded view of the room and keeps her safe from melee.

- Place the pit traps in the gaps between these raised platforms. This forces characters to either engage the skeletons head on or fall through the concealed pit traps.

- Replace one of the lamia’s spells to make her more threatening at range, which is how she’ll engage the party for the most of the encounter. Swap scrying with scorching ray. The party might even use the tall terrain as cover to keep out of her line of sight, thus preventing her from casting scorching ray at the concealed characters.

Instantly, the encounter is improved by creating more diverse terrain and specifying the starting position of each monster. Did you notice another element of terrain that makes this encounter unusual? The distance at which the enemies are encountered massively changes the way the encounter plays. This is just another facet of positioning. Spacing out the skeletons in groups makes each pair of pillars into a micro-encounter that the characters have to deal with in order to reach the lamia. Consider starting an encounter in the wilderness at an extreme range of 1,000 feet or more to give the adventurers and their foes options as one approaches the other, possibly with a hail of longbow shots. This could turn a combat encounter into a chase, or even an attempt to hide and sneak away.

Monsters and Hazards

A good tactical encounter uses two or even three different types of monsters. They don’t have to be different species, but they should serve different roles. In other words, you should have several different groups of monsters that do different things. In every encounter, try to have at least two groups of monsters with different strengths, such as:

- Minions (melee), a group of weak enemies that specialize in melee combat; individually, they have a challenge rating several points lower than the party’s level.

- Minions (ranged), a group of weak enemies that specialize with ranged weapons or spells; individually, they have a challenge rating several points lower than the party’s level.

- Minions (support), a group of weak enemies that use magic to hinder enemies or buff allies; individually, they have a challenge rating several points lower than the party’s level.

- Elite, a strong monster that the characters will have to spend several turns defeating. It has a challenge rating roughly equal to the party’s level.

- Boss, the leader of minions and elites; usually the encounter’s strongest monster, but sometimes it uses ranged attacks and spells to support its minions and elites. It has a challenge rating one or two points higher than the party’s level.

Design Tip: Magic Items

As the characters gain magic items, they start to break the encounter building guidelines. You can stretch the definition of elite and boss monsters to be stronger and stronger as the characters gain magic items and other forms of power beyond simply gaining levels.

The monsters in the Monster Manual and Basic Rules don’t use these unofficial classifications. They’re just broad categories to help you think of monsters in different ways. When a party gets stronger, you can turn elite monsters that the characters faced several levels ago into minions to show how much more powerful they’ve become. You can enhance the importance of the terrain by filling your encounter with monsters with different combat roles (melee, ranged, or support). This requires your players to make decisions; what enemy is more important, the big beefy monster in our face, or the creature buffing it? Or is it the minions shooting at us from afar?

Don’t overlook the power of traps and environmental hazards, either. Even though traps and hazards are stationary, they can be put to great use in combat. Monsters can try to push characters into burning braziers to deal damage, or into deep pits to temporarily remove characters from combat for a turn or two so that they can focus on defeating other adventurers. Concealed traps can shake up an otherwise predictable combat with surprising new information, and make your players consider precisely where their characters want to move.

In the example of the ancient treasure vault above, there are two categories of monsters and one type of trap. The lamia is the boss of this encounter, and she has a group of ranged minions spread out across the battlefield. There are several spiked pit traps that force the characters to move through the room in an unorthodox fashion, or risk taking damage. Following this rule of three different “moving parts” in an encounter is a good strategy. It’s a good level of complexity that’s still easy for everyone at the table to casually keep track of.

Five different monsters or hazards is a good upper limit for a climactic battle. Playing a battle with more than five moving parts is mentally exhausting for all but the most seasoned tactical veterans.

Win Conditions

Most D&D encounters are presented like a fight to the death. Monsters appear, you kill them, the encounter ends. But D&D doesn’t have to be this way; not every fight has to be to the death. In fact, in the real world, we tend to think of people who kill their enemies senselessly as war criminals and psychopathic monsters. If you create encounters where murdering everything in sight is the only way to win, then you will be turning your characters into bloodthirsty monsters. Reluctant bloodthirsty sociopaths, at best.

The fact of the matter is that most living creatures don’t want to die. Even for a cause they believe in, all but the most stalwart zealots would rather flee than die. Consider filling your encounters with more enemies than usual, but have them surrender once they’re reduced to one-quarter their maximum hit points. Some Dungeon Masters consider the “top half” of their foes hit points to be nothing but raw luck and morale, and that a creature only takes a physical wound once they’re reduced to half their hit point maximum. The term “bloodied” represents that an attack has finally drawn blood. From there on out, more and more of their hit points represent their ability to take physical blows. If you follow this assumption, then a creature reduced to one-quarter its hit point maximum has taken a grievous wound that could kill it if it chooses to fight further. That’s when most fighters raise up their hands and scream, “Mercy!”

You could go even farther with this concept of killing only when necessary. Maybe the enemy force controls a crucial location like a castle’s gatehouse or a ritual circle, or an item like a dragon’s egg or a magic artifact. By capturing that item or location, you can force the rest of the foes to retreat or surrender. Maybe the characters are attacked while traveling from point A to point B, and the only thing they have to do to win the encounter is to escape to a certain point on your map, allowing them to elude their ambushers. Or perhaps an encounter occurs while a gigantic door is being opened, an elevator is descending, or a wizard is trying to complete a minute-long ritual. Then, the only goal is to survive until the countdown clock is finished. Finally, some foes are only fighting because their commander has forced them to. If you defeat the boss, then the rest of the minions will scatter. No matter what victory conditions you include, be sure to make sure your players know about them. You could do it directly by telling them flat-out what the victory conditions are, or indirectly by having the enemies talk about what they want in a place that the characters can overhear them.

All of these alternate victory conditions help you create battles that are more tactically diverse, but they also help you and your players understand the role of violence in your story. Even though movies and video games see our heroes mowing down faceless grunts by the thousands, such wholesale slaughter is rare in the real world. Is that the kind of story you want to tell?

DMing Tip: Awarding Experience Points

If your characters insist upon killing enemies that they don't strictly have to in order to overcome a challenge, it may be because you only award XP for enemies that they kill. Try telling them that they'll gain full experience for defeating all the enemies in an encounter no matter how they clear an encounter, even if they didn't kill all of the creatures in it. This is a behavior that video games instill in a lot of players, since XP is only awarded for enemies defeated in combat. This trick can break them of that murderous habit!

Don’t go Overboard

One of the great downfalls of tactical combat is that DMs and designers invariably get too excited for their own good. They throw in tons of terrain, position every monster perfectly, add a dozen different monster types, and top it all off with an esoteric win condition. Throwing everything but the kitchen sink into an encounter is actually bad design. Adding too many flavors that are exciting on their own into the stew creates a muddy mess that confuses the palate. The same is true for elements of a tactical encounter.

If you’re just starting out making tactical encounters, include just one interesting element. See how it works on its own. Start small, and grow bigger. Let your encounters fluctuate between “simple (with a twist)” and “a hair shy of mind-bendingly complicated.” This variety will actually make each encounter more fun for you and your players, because it gives them variety.

Advanced Tactics

There are more advanced tactics to consider when building encounters for your campaign, but they go beyond the scope of this simple primer. Let’s save topics like synergy, tactical roleplaying, and tactical ability checks for another day. Until then, try making your own tactical encounters using maps from Tactical Maps Reincarnated as inspiration!

Let D&D Beyond's digital dice handle the dice rolling while you focus on the tactics! Use D&D Beyond Encounters to plan for combat encounters and run them!

Create A Brand-New Adventurer Acquire New Powers and Adventures Browse All Your D&D Content

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus, and the Critical Role Explorer's Guide to Wildemount, a member of the Guild Adepts, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and other RPG companies. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his fiancée Hannah and their animal companions Mei and Marzipan. You can find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

James Haeck is the lead writer for D&D Beyond, the co-author of Waterdeep: Dragon Heist, Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus, and the Critical Role Explorer's Guide to Wildemount, a member of the Guild Adepts, and a freelance writer for Wizards of the Coast, the D&D Adventurers League, and other RPG companies. He lives in Seattle, Washington with his fiancée Hannah and their animal companions Mei and Marzipan. You can find him wasting time on Twitter at @jamesjhaeck.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2020Love that combat tracker!! Super easy to use, especially if you've shared stuff with others!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2020Wow this is really helpful! I’ve wanted to make my campaign more tactical for a while, and now I know how! Thanks.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2020Super good. A few typos though. 'At beast' should say at least and for the minions it says 'they a challenge rating'. It should say they have a challenge rating. But still super fun and interesting.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2020Why do the dice on the video make noise but not mine? Part of the satisfaction I get from rolling dice on tabletop simulator is not only the dice bouncing and rolling, but the sound effects too! I need click clack of dice rolling D&D Beyond!

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2020Thank you! Those errors have been resolved.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 8, 2020Awesome ideas! From the beginning, most of the enemies in my campaign have preferred retreat to death, and recently, I've been trying to add more variety to the terrain in combat encounters. The idea of adding enemies with different skill sets as described here will be really useful, and so will unique paths to victory. Implementing traps is a challenge for me, but I should start looking into that possibility.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2020Really great. I recently started my own campaign, instead of running a published one, and all these posts are helping.

Also, small typo: If you create encounters were murdering everything in sight is the only way to win

Many Thanks!

Aragorn

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2020Solid advice overall about terrain/trap mechanics and using enemy abilities with the idea of specific roles and synergies in mind. I think touching on the enemy mindset and resolve in an encounter is the key point of the takeaway from this article. This the most underplayed aspect of roleplaying in my opinion

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2020An excellent article. I really love theater of the mind, but tactical combat on a map has a unique charm.

Just adding a few elevation changes and a little cover add a whole new dimension to gameplay.

With the example encounter, i immediately started think about how a PC could best use the cover of the different skeletons’ platforms, or what tricks the party’s spellcasters might have up their sleeve. With some simple changes, the situation starts evoking these strategic thoughts.

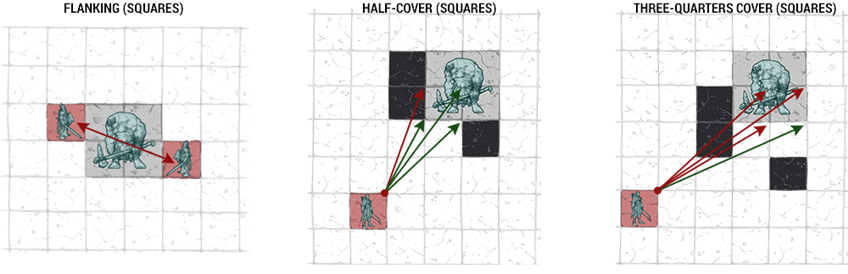

As an aside I recognize that positioning chart. Always though it was a good one, got the point across well!

For those thinking of using the optional flanking rule, I recommend a +2 to hit bonus, instead of advantage (like in old editions), so you can stack it with effects like faerie fire.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2020Same for me. Thanks for the article. I think my next encounters will get a pinch of flavour.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2020Ive found a useful strategy is to refer in your mind to your experience on whats tweaked your imagination in the past, for example. I am a returner to DnD after just shy of 40 years. Since playing last my minds eye has been filled with experiencing the colour of WoW from the very start, some of the tactical encounters in that game transpose so well to DnD - BUT even better here as you are no longer constrained by a computer game...so have those pictures of gorgeuous scenenry in your mind but fill the ecnounter with realistic challenges and monsters rather than the tired groups that you just attack and kill

Try and walk round what youve built in your mind - what does it look like? Would the boss stand there....would it place an ambush here....how will the characters react?

And DONT plan for their magical items and creativty plan for the monsters only...,there is nothing more epic for a party than to defeat a foe in a way they can guess you never intentioned.

I recently had a party battling a group of troglodytes, they had managed to shut a gate on a superior sized and strength party, but had just run out of spells and the trogs were breaing through the gate....so they ran...previously to get to the area they had stumbled through a corridor with a weakened floor that had collapsed into a deep pit....so they had to jump it..They all failed (and the jump wasnt hard...just bad dice) they all fell and took some nasty damage but didnt die. The Trogs came pouring up the stairs behind them...the caster put an illusion over the pit making it to appear solid....they failed their save and tumbled in past the party...killing most - leaving the boss badly wounded he was quickly dispatched....

Twas a laugh...

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 9, 2020good Ideas

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020A really great article. Even after 22 year, I liked that " push " toward good tactical planning.

Thx

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020While i really like these ideas and were already trying to push for those in my games.... i will say that, by experience, this type of encounter is a nightmare for melee people and casters would just breeze through it like it was nothing, because their spells have easily more ranges. so basically your "tactical" encounters, just became tactical for the melee people, not the casters ! for the casters, its business as usual.

this is the problem with d&d in general and that is the casters are much more powerfull then the melee guys. the melee guys often only have one trick up their sleeves and that trick isn't really working in many cases. while some casters have only one trick up their sleeves but its a good trick that works most of the time.

exemple...

i had this idea of zombies getting in from a far, but that clever player warlock... eldritch blast is 120 feet. taking lance invocation and sharpshooter feat... his range is suddently 480 feet. so he tells me, i just pot shot every zombies as they approach while the rest of the gang does their thing... 120 feet is already a great distance.... but 480 ! i was stunned... so i was rolling dice for zombies, telling him that some falls and others seems to resist his blast and get closer. but by the time they got to him or the group... there was about 4 left when i was gonna swarm them up.

another exemple... same shit...

Boat fights, the same warlock ends up shooting the guy on the other boat that helms the wheel. because 480 feet is still much better then any canons they have on board. so yeah, no boat mechanics for us, that sole player can keep the boat in range and unmanned all the time.

those are just two exemples of how much casters and their long range just kills the game mechanics. why do you need guns when your mage or warlock can shoot more then you at better range !

thats my problem with tactical encounters right now...

Melee fighters are like (am i in range ? no, i move, am i in range ? no, damn ! next turn then !)

Casters are like (my cantrip goes 120 feet, am i in range? yes, i shoot then move behind cover)

thats it, the tactical elements even though terrain elevations changes or whatever is always played this way.

flying monsters, same as above...

burrowing monsters, as as above.

horde of zombies, same as above.

Your exemple of combat, same as above.

casters wont care about elevation, nor your traps as they don't really move around the board.

the only ones who will care are fighters and melee, who instead of trying to get there, will just lay back and wait for casters to do their job.

no the best way to make an encounter challenge both parties, is to have the map do something to both of them.

unfortunately that requires much much more thought then just elevation and a few spike traps.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020If spellcasters are dominating your combat encounters, then consider creating terrain that aids the monsters' ability to hide from ranged spells and attacks. Or, you could include spellcaster enemies that are able to cast spells like sanctuary, Otiluke's resilient sphere, or even globe of invulnerability on their allies. That way, major creatures are safe from spellcasters unless someone is able to close in and break their concentration.

And, if you're a martial character, make sure you have a backup ranged weapon so you can attack from range as well.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020@DnDPaladin.

This sounds more like a ranged combat issue, than a Spellcaster issue. The sound advice is to do more with cover, line of sight, and distance of engagement, but i know that’s a truism you probably heard before.

If one or two members of the party (like your Warlock) are really standing out as that much, enemies should either target, or avoid them specifically. I’m don’t mean get “revenge” on them for being effective, just that it is entirely logical for monsters (even simple-minded ones) to counter the enemy that is doing the most harm to them.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020The problem I have is communicating information about terrain and positioning whilst our group is online. I've never been good with battle maps or anything like that, so when I start making things more complicated, inevitably it ends up slowing things down as people have to ask loads of questions to make sure they're picturing it right! I've started making my fights more cinematic and less bogged down in the details which works for my group, as most of the time they don't want a tactical challenge, but just want to feel powerful and cool.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020One solution to help with that would be to use a vtt.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 10, 2020Everyone forgets Geas has a 1 minute cast time and isn't really a combat spell.

-

View User Profile

-

Send Message

Posted May 11, 2020Bit of a bone to pick with the proposed design sample.

As it stands ranged attacks in 5e are just better than melee in many situations, being able to attack from range and avoid the need to get up close with enemies (who are often more dangerous in melee), as well as having an accuracy boost in many cases. They also have a perfectly good backup melee if it came to that (rapier or double shortswords). And ranged fighters can ALSO use cover to either boost their AC, or avoid attacks entirely (as you mentioned). Also rogues can do the abusive "hide and attack with advantage from behind cover" trick too.

Avoid things that make ranged attacks the only option, if you can help it. Same way you should avoid anti-magic fields blanketing a battlefield.